The life and death of a Soviet-era search for longevity

From the Montreal Gazette: "Want to prolong life? To start with, you need three corpses from healthy young men accidentally killed in within the previous 12 hours. Then you remove tissue from their spleen and bone marrow and grind these in a mortar with saline solution. Centrifuge this mixture and inject the fluid that rises to the top into a horse, goat or rabbit. Three to five days later, bleed the animal and collect the serum, the liquid part of the blood that does not contain any cells. Then inject what is now termed “anti-reticular cytotoxic serum (ACS)” into a person to treat disease or just increase longevity. Soviet physician Alexander Bogomolets came up with this scheme in 1934, drawing the attention of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, who was interested in increasing life expectancy, mainly his own. Stalin appointed Bogomolets director of the Institute of Clinical Physiology in Kyiv, where ACS was produced for wide distribution."

Everything we think we know about spies is wrong

From Literary Hub: "In the movies, spies are usually ripped hunks who carry lots of gadgets, like James Bond and Jason Bourne. That’s rarely the case in real life, however. When the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA, was established in haste at the outset of WWII, the spies tapped to join were librarians, professors, and researchers quite literally pulled from college campuses. They proved to be uniquely suited to the job of discerning intel buried in mountains of documents, traveling to far-flung archives in occupied territories and weaseling their way in, and generally slipping under the radar as the bookish types they were, in order to gather and deliver highly sensitive information. Some of them were sent to learn the real rules of spycraft at the training schools of the Special Operations Executive, Britain’s clandestine intelligence agency.”

Mysterious white substance smeared on 3,600-year-old mummies is world's oldest cheese

From Live Science: "A mysterious white substance smeared on the heads and necks of 3,600-year-old mummies in China is the world's oldest cheese. Researchers initially discovered the enigmatic material smudged on several of the mummies buried at the Xiaohe Cemetery in northwestern China's Tarim Basin about two decades ago. Now, DNA tests have revealed that the mystery goo was kefir cheese, a probiotic soft cheese, and that it was produced using cow and goat cheeses thousands of years ago, according to a study published in the journal Cell. The cheese contained several bacterial and fungal species, including Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens and Pichia kudriavzevii, both of which are found in modern-day kefir grains. These grains are "symbiotic cultures" that consist of a mix of bacteria and yeast, which ferment milk into cheese."

Inside the world’s weirdest library, now open to the public

From the Guardian: "A mysterious cosmic emblem hangs over the entrance to a building in Bloomsbury, at the heart of London’s university quarter. Depicting concentric circles bound by intertwined arcs, it represents the four elements, seasons and temperaments, as mapped out by Isidore of Seville, a sixth-century bishop and scholar of the ancient world, as well as patron saint of the internet. What lies within is not a masonic lodge, though, or the HQ of the Magic Circle, but the home of one of most important and unusual collections of visual, scientific and occult material in the world. Long off-limits to passersby, the Warburg Institute has now been reborn, after a £14.5m transformation, with a mission to be more public than ever. The institute was founded in Hamburg at the turn of the 20th century by pioneering German art historian Aby Warburg, whose work focused on tracing the roots of the Renaissance in ancient civilisations, mapping out how images are transmitted across time and space."

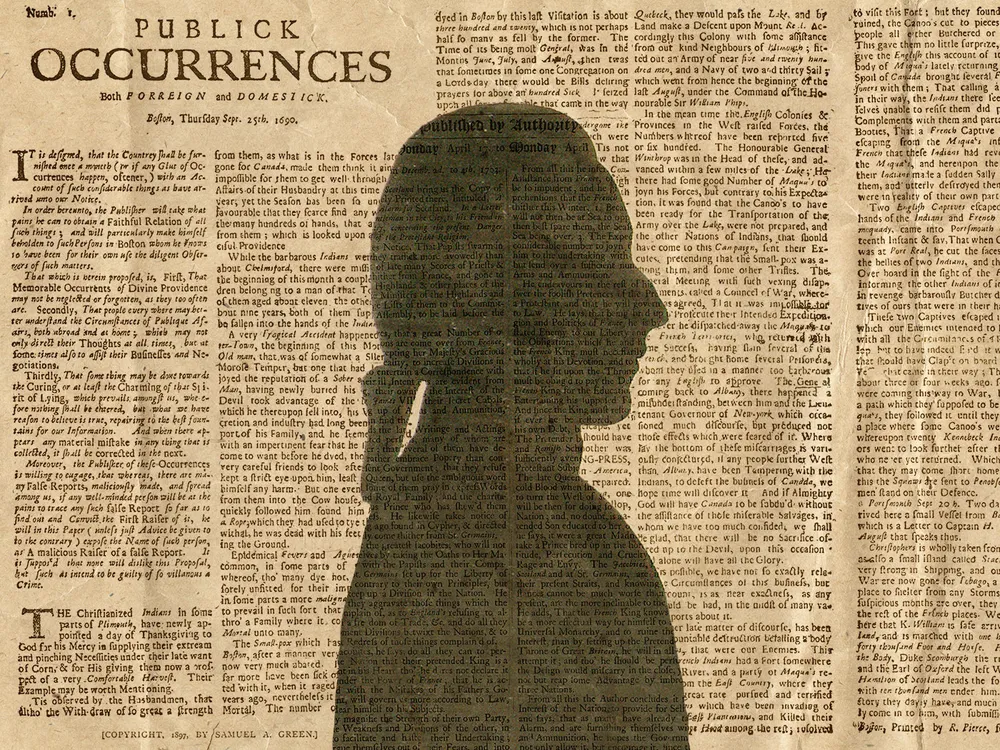

Why the debut issue of America’s first newspaper was also its last

From the Smithsonian: "Once you get over the archaic language, the first newspaper published in North America seems largely innocuous, its pages filled with reports on dramatic events like a smallpox outbreak, a devastating fire and troop movements. Yet Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick—issued in Boston by English expatriate Benjamin Harris on September 25, 1690—so angered colonial authorities that they shut down the paper after just four days. The first issue of the four-page publication also proved to be its last, and it took another 14 years for homegrown journalism to return to British America. Harris was a publisher and writer who had fled England amid backlash for printing anti-Catholic pamphlets. Settling in Boston in 1686, he’d opened a popular coffeehouse where locals gathered to discuss current events and the latest books. As colonial printer and historian Isaiah Thomas later said, Harris was “a brisk asserter” of the right to free expression.”

Girl who used to be paralyzed visits the nurse who took care of her

Girl who used to be paralyzed visits the nurse who took care of her pic.twitter.com/zcW5UtPbux

— Historic Vids (@historyinmemes) September 24, 2024

Acknowledgements: I find a lot of these links myself, but I also get some from other newsletters that I rely on as "serendipity engines," such as The Morning News from Rosecrans Baldwin and Andrew Womack, Jodi Ettenberg's Curious About Everything, Dan Lewis's Now I Know, Robert Cottrell and Caroline Crampton's The Browser, Clive Thompson's Linkfest, Noah Brier and Colin Nagy's Why Is This Interesting, Maria Popova's The Marginalian, Sheehan Quirke AKA The Cultural Tutor, the Smithsonian magazine, and JSTOR Daily. If you come across something interesting that you think should be included here, please feel free to email me at mathew @ mathewingram dot com