This Amazon tribe's hearts and brains age more slowly

Hi everyone! Mathew Ingram here. As many of you probably know, I am able to continue writing this newsletter in part because of your financial help and support, which you can do either through my Patreon or by upgrading your Ghost subscription to a monthly contribution. I enjoy gathering all of these links and sharing them with you, but it does take time, and your support makes it possible for me to do that. And I appreciate it, believe me! If you like this newsletter, please share it with someone else. Thanks for being a reader!

Members of this Amazon forest community have hearts and brains that age more slowly

From the BBC: "As Martina Canchi Nate walks through the Bolivian jungle, red butterflies fluttering around her, we have to ask her to pause - our team can’t keep up. Her ID card shows she’s 84, but within 10 minutes, she digs up three yucca trees to extract the tubers from the roots, and with just two strokes of her knife, cuts down a plantain tree. She slings a huge bunch of the fruit on her back and begins the walk home from her chaco - the patch of land where she grows cassava, corn, plantains and rice. Martina is one of 16,000 Tsimanes (pronounced “chee-may-nay") - a semi-nomadic indigenous community living deep in the Amazon rainforest, 600km (375 miles) north of Bolivia’s largest city, La Paz. Her vigour is not unusual for Tsimanes of her age. Scientists have concluded the group has the healthiest arteries ever studied, and that their brains age more slowly than those of people in North America, Europe and elsewhere."

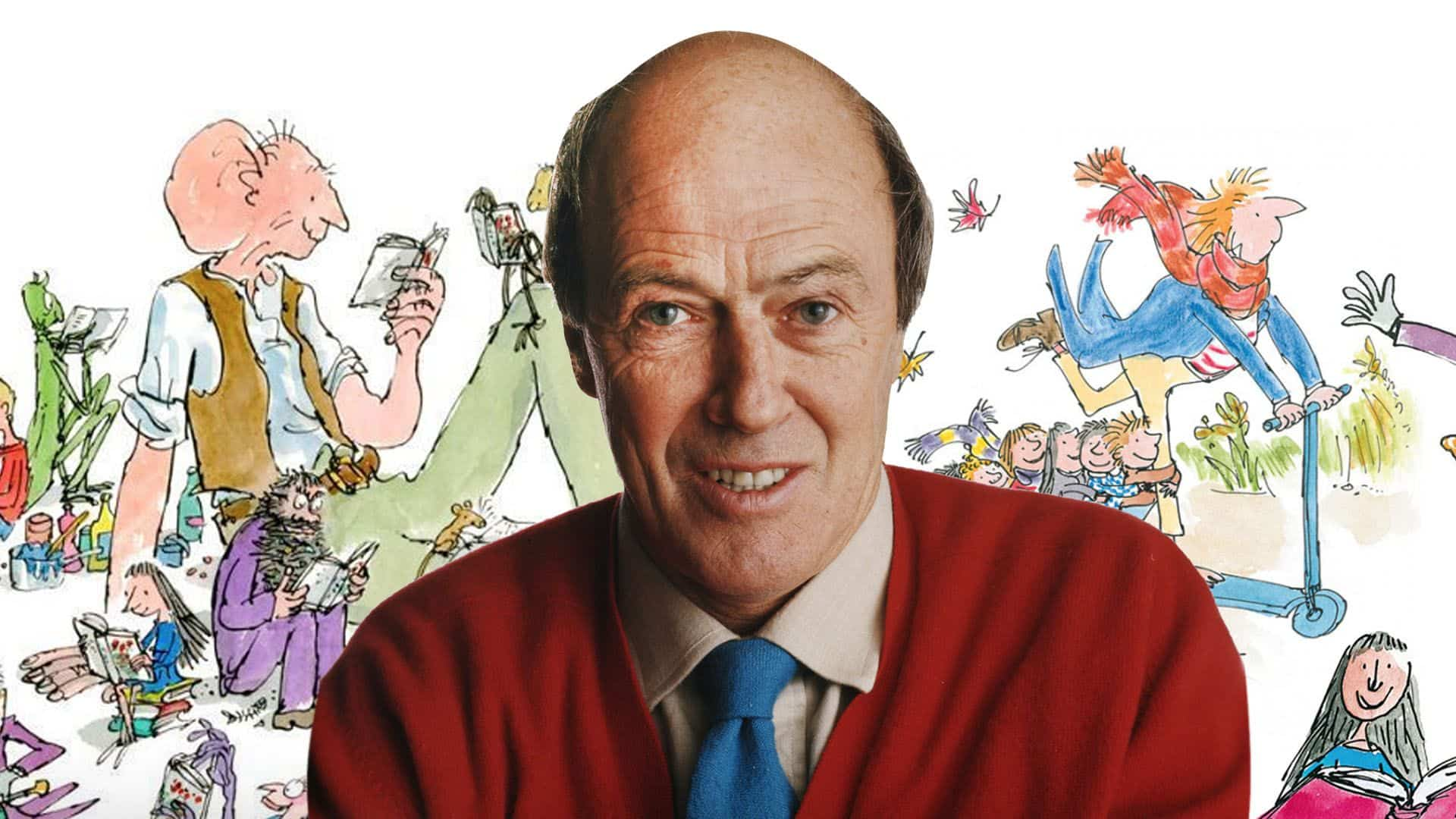

Author Roald Dahl helped invent a brain shunt for children with hydrocephalus

From Wikipedia: "In 1960, Dahl's son Theo developed hydrocephalus after being struck by a taxicab. A standard Holter shunt was installed to drain excess fluid from his brain. However, the shunt jammed too often, causing pain and blindness, risking brain damage and requiring emergency surgery. Till, a neurosurgeon at London's Great Ormond Street Hospital for children, determined that debris accumulated in the hydrocephalic ventricles could clog the slits in the Holter valves, especially with patients such as Theo who had bad bleeding in the brain and brain damage. Dahl knew Wade to be an expert in precision hydraulic engineering, from their shared hobby of flying model aircraft. (In addition to building his own model aircraft engines, Wade ran a factory at High Wycombe for producing precision hydraulic pumps.)"

This airline is almost 30 years old but has never flown a single plane anywhere

From Now I Know: "In the spring of 1989, an immigrant from Latvia named Igor Dmitrowsky founded Baltia Airlines, a start-up carrier offering flights from New York City to Leningrad. And yet, Baltia wasn’t able to do anything, at least not right away, since it had no planes, no flight crews and no financing. The good news: given its license to fly to the Soviet Union, finding money shouldn’t have been a problem. But then, something went wrong: the Soviet Union collapsed. Baltia had to reset, taking a different approach to the changing world — a reset that cost them another five years. In 1996, Baltia was finally able to get the right to fly to Saint Petersburg — but again, the airline didn’t have any airplanes. Finally, in 1998, they had the funding to acquire an old 747; a year later, they had enough cash on hand to hire flight crews, secure gate access at New York’s JFK airport and all the other stuff you need to make a plane safely go up and come back down. It looked like they may finally make it to the friendly skies. They didn’t."

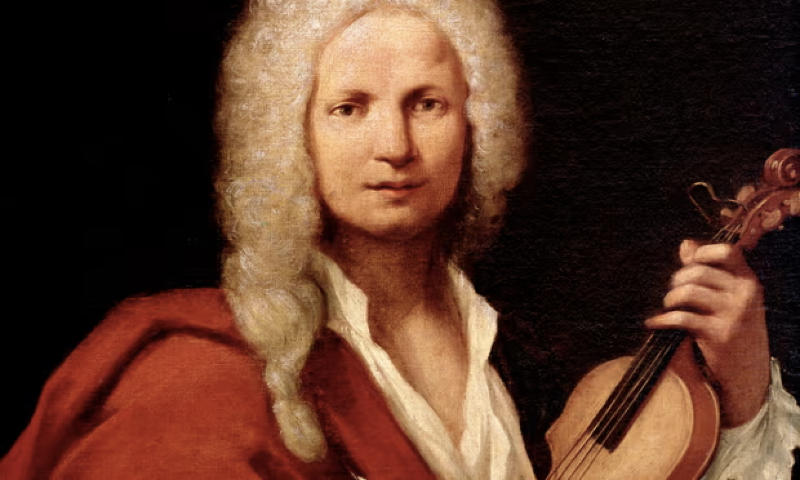

Vivaldi taught Venetian orphan girls — did they help write his music?

From The Guardian: "One day, I pluck the nearest book from the shelf and start flicking through. I land on a line about an orphanage in Venice. It says Antonio Vivaldi taught here, that his students went on to become some of the greatest musicians of the 18th century. I learn that the orphanage was created in part because illegitimate babies were being drowned in the Venetian canals. I discover that Vivaldi spent almost his entire career working at the Pietà and composed most of his pieces while there. But of the hundreds of girls and women who studied there, one name keeps rising to the surface: Anna Maria della Pietà. A prodigy violinist, she was Vivaldi’s favourite student. He composed many pieces just for her. It was in this experimental environment, with a plethora of talented female musicians to test ideas with, and Anna Maria by his side, that Vivaldi was able to perfect a new form of music: the concerto, most famously realised in his Four Seasons. Is it possible that these girls helped Vivaldi compose his work?"

What it's like to live in one of the hottest cities on the planet

From The Atlantic: "Last month, I visited the emergency room of Mayo Hospital, the largest hospital in Pakistan. For more than 150 years, it has stood just outside the Old City of Lahore, not far from the marble domes of the Badshahi Mosque. Every day, more than 1,000 people fill its wards. No one is turned away. Patients come from all corners of Lahore, from the sugarcane fields outside the city and far-off villages. In the lobby, some of them rolled past me in wheelchairs or arrived on makeshift stretchers. There was terrible wailing and occasional screaming. The 49-year-old head of the emergency department, Dr. Yar Muhammad, walked me over to where patients were categorized according to urgency. Earlier this summer, he had added a new intake counter. It is devoted exclusively to patients afflicted by Lahore’s extreme heat. In May, temperatures rose into the 120s. Schools were closed so that kids would not get heatstroke."

Scientists think they have isolated the brain pathway behind the placebo effect

From Lab & Life: "A research team led by The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has discovered a pain control pathway that is crucial to placebo analgesia — where the expectation of pain relief leads to pain alleviation without therapeutic intervention. Their research, published in Nature, provides a new framework for investigating the brain pathways underlying other mind–body interactions and placebo effects beyond the ones involved in pain. The placebo effect — feeling an improvement in your health after taking a ‘sham’ treatment — has been documented as a very real phenomenon for decades. This explains why individuals in the control group of clinical trials may feel their symptoms subside; in fact, it’s thought that some individuals in the ‘actual’ treatment group also experience the placebo effect. This is one of the reasons why clinical research of therapeutics is so difficult, and why it’s so important to understand what is happening in the brain of someone experiencing the placebo effect.

This 16-cylinder Audi was designed in the 1930s but built in 2024

A car designed in the 1930s, constructed in 2024.

— Science girl (@gunsnrosesgirl3) August 22, 2024

pic.twitter.com/q5MF0ihExD

Acknowledgements: I find a lot of these links myself, but I also get some from other newsletters that I rely on as "serendipity engines," such as The Morning News from Rosecrans Baldwin and Andrew Womack, Jodi Ettenberg's Curious About Everything, Dan Lewis's Now I Know, Robert Cottrell and Caroline Crampton's The Browser, Clive Thompson's Linkfest, Noah Brier and Colin Nagy's Why Is This Interesting, Maria Popova's The Marginalian, Sheehan Quirke AKA The Cultural Tutor, the Smithsonian magazine, and JSTOR Daily. If you come across something interesting that you think should be included here, please feel free to email me at mathew @ mathewingram dot com