The nuclear fusion test facility that was never turned on

On Friday, February 21, 1986 a group of 300 scientists, engineers, contractors and government officials gathered for a dedication ceremony at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. After final diagnostic tests, the "Mirror Fusion Test Facility-B" (MFTF-B) completion was celebrated, and a letter from John Herrington, Ronald Regan's Secretary of Energy was presented to program director T. Kenneth Fowler extending his congratulations on a job well done. The 350 ton magnet was encased in stainless steel built in a distinct “yin-yang” shape, and its interior was cooled to temperatures of 425º F below zero, by pumping liquid helium through the vessel. Thirty miles of copper and niobium-titanium wire were wound over the course of a year to make the magnet’s conductor. The magnet was capable of generating magnetic fields 150,000 times that of Earth’s that could contain the 500-million Kelvin degree plasma generated by the fusion device. But on the very same day she was dedicated, after nearly a decade of development and nearly a billion dollars of funding, the project was shut down.

The real story of Rosie the Riveter

The usual history says that “Rosie the Riveter was the star of a campaign aimed at recruiting female workers for defense industries during World War II, and she became perhaps the most iconic image of working women.” This undergirds Rosie’s status as feminist icon, celebrated everywhere from mugs and t-shirts to Beyoncé’s Instagram and children’s picture books. In fact, as rhetoricians James J. Kimble and Lester C. Olson have demonstrated, “We Can Do It” was produced by artist J. Howard Miller as part of a work-incentive campaign for the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. One of many genres of propaganda produced during WWII, work-incentive images were designed to promote wartime productivity and ease tensions between labor and management, averting potential strikes. Miller’s image was not a recruitment poster, and the figure it depicted was not named “Rosie the Riveter.” In fact, she had no name at all.

After a 1935 tragedy, a priest vowed to teach kids about menstruation

Nine decades ago, a 13-year-old girl’s death by suicide after getting her first period sparked an effort to educate kids about their bodies to prevent fear and confusion — a once-settled issue that new legislation in Florida is resurfacing. That teenagegirl in 1935, who had never been taught about menstruation, thought her period was a “terribly shameful, retributive disease,” says one account of the history. The fact that this British girl who believed she had a venereal disease had no one to teach her about her body, and no one to talk to, deeply impacted Chad Varah, the 23-year-old deacon who officiated her burial. Standing over her grave, Varah, who later became a priest, promised to devote his life to battling ignorance and despair about sexual issues. “Little girl, I never knew you, but you have changed my life. I shall teach kids what I learnt when I was younger than you. …” he said at her gravesite in England, according to the Samaritans of Rhode Island, a chapter of the suicide-prevention charity he later founded.

Railroad chapel cars brought God to the people

Railroad chapel cars, which were first used in the United States by Protestant denominations, were mobile churches that traveled from town to town, providing religious services to the people living in remote communities where there was no church. The first American chapel car was built by the Episcopal Church in 1890 and was followed very quickly by several others operated by the Baptists. Researchers trace the origins of American chapel cars to the late nineteenth century, when the growth of the railroad industry made it possible to travel across the country quickly and efficiently. Hundreds of small towns had sprung up along the rail lines; most were too small to support clergy and had no dedicated houses of worship. The earliest true ‘church on rails’ was the train of three beautiful Russian Orthodox church cars that moved with the construction gangs first along the Trans-Caspian and then along the Trans-Siberian Railroad.. There were no pews because the congregation worshipped standing up.

The man who hid in the jungle for 30 years

December 1944: in the final months of World War Two, a Japanese lieutenant named Hiroo Onoda was stationed on Lubang, a tiny island in the Philippines. Within weeks of his arrival, a US attack forced Japanese combatants into the jungle – but unlike most of his comrades, Onoda remained hidden on the island for nearly 30 years. The Japanese government declared him dead in 1959, but in reality, he was alive – committed to a secret mission that had instructed him to hold the island until the imperial army's return. He was convinced the whole time that the war had never ended. When he returned to Japan in 1974, Onoda received a hero's welcome – he was the last native Japanese soldier to return home from the war, and his memoir, published soon after, became a bestseller. His experience is told in Arthur Harari's epic, three-hour film Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle, which has won critical acclaim and created controversy since its premiere.

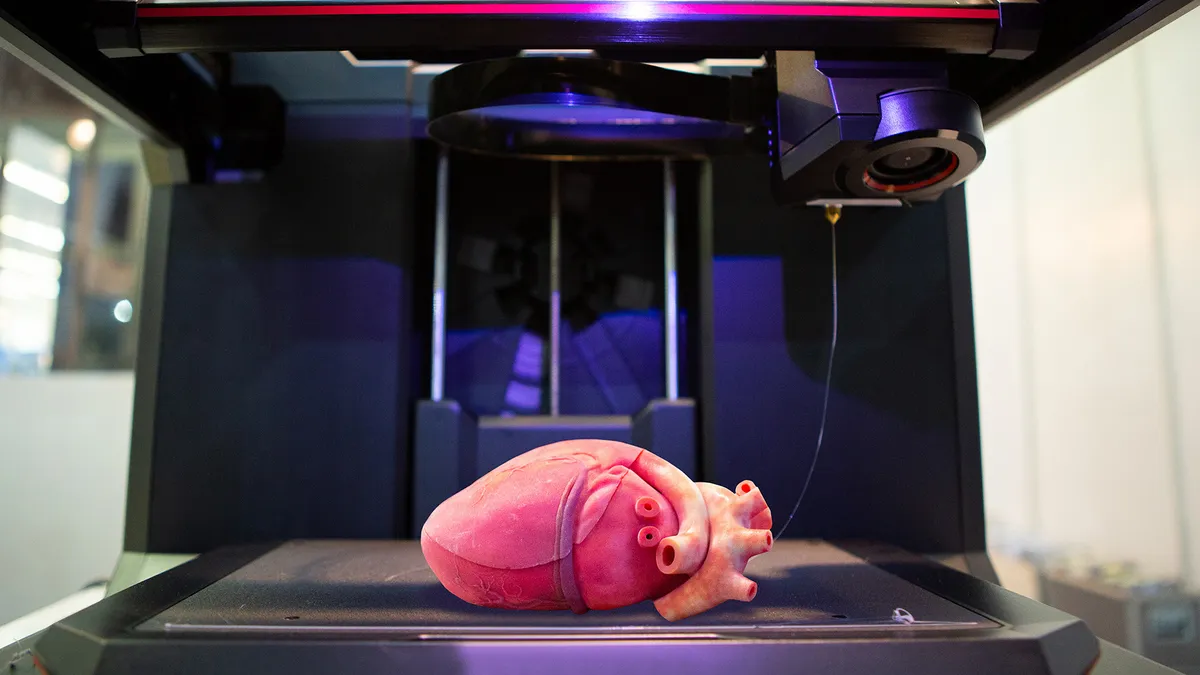

Scientists 3D print living cells inside the body

Three-dimensional bioprinting uses bio-inks mixed with living cells to print natural tissue-like structures. Currently, this technology can be applied to various research fields, including tissue engineering and drug development. Now, the University of New South Wales, Sydney (UNSW Sydney) engineers have created a tiny, adaptable soft robotic arm that can 3D print biomaterial directly onto internal organs. Published in Advanced Science on February 19, the research was conducted by Dr. Thanh Nho Do and his Ph.D. student, Mai Thanh Thai, in collaboration with other researchers from UNSW, including Scientia Professor Nigel Lovell, Dr. Hoang-Phuong Phan, and Associate Professor Jelena Rnjak-Kovacina. The newly developed 3D bio-printed device, known as F3DB, can directly transfer multilayered biomaterials onto the surface of internal organs and tissues. They tested the F3DB inside an artificial colon and a pig's kidney.

Waipuhia Falls in Hawaii is also known as "The Upside Down Waterfall"

Waipuhia Falls was aptly nicknamed Upside Down Waterfall and is visible from the Pali expressway in Oahu, Hawaii.

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 4, 2023

Several other 'reverse waterfalls' can be found in the world: https://t.co/9mMym2JfAR

[📹 https://t.co/mGcASozZ9u]pic.twitter.com/AoKCvy1w21