How the Great Cranberry Scare of 1959 set off a panic

From History.com: “On November 9, 1959—just two-and-a-half weeks before Thanksgiving—the U.S. secretary of Health, Education and Welfare made a startling announcement: some cranberries grown in the Pacific Northwest may have been contaminated by a weed killer that could lead to cancer in rats. This meant that cranberry sauce, a popular staple of Thanksgiving dinners, might not be on the menu anymore. Thus began the cranberry scare of 1959, a crisis that temporarily crashed the cranberry market and sent Americans scrambling for alternative fruit-based dishes for Thanksgiving (Life magazine provided a few interesting suggestions, including pickled watermelon rind).”

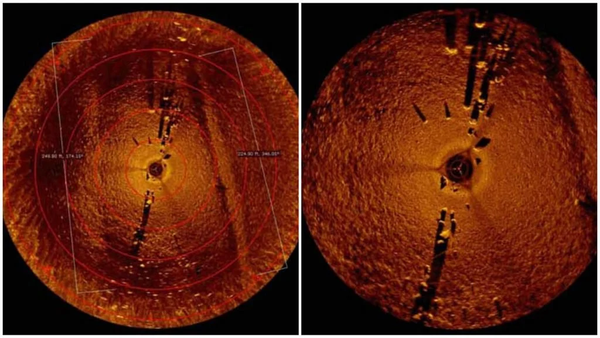

Why we probably won’t find aliens anytime soon

From Scientific American: "Are we alone in the universe? The answer is almost certainly no. Given the vastness of the cosmos and the fact that its physical laws allowed life to emerge at least one place—on Earth—the existence of life elsewhere is effectively guaranteed. But so far, despite generations of looking, we haven’t found it. In that time, however, we’ve arguably learned enough to declare that, while we may not be alone, the interstellar gulf between us and our nearest neighbors effectively puts us in an isolation ward. This doesn’t mean we should stop looking—only that we should manage our expectations and prepare for a long and lonely voyage through space and time before meeting them, either virtually or physically."

Study says great apes may have cognitive foundations for language

From Popular Science: "You see a cat chasing a mouse. You probably don’t realize it, but as soon as you catch sight of this scene unfolding, your brain makes a key distinction between the cat and the mouse: It identifies who’s chasing, and who’s being chased. This capacity to distinguish between the “agent” (the entity performing an action) and the “patient” (the entity upon which that action is being performed) is called “event decomposition,” and it’s long been thought that it was unique to humans. However, a new study published in PLOS Biology on November 26 suggests that this is not the case: great apes (specifically gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans) also seem to track events in the way that we do, distinguishing between agent and patient."

Hi everyone! Mathew Ingram here. I am able to continue writing this newsletter in part because of your financial help and support, which you can do either through my Patreon or by upgrading your subscription to a monthly contribution. I enjoy gathering all of these links and sharing them with you, but it does take time, and your support makes it possible for me to do that. And I appreciate it, believe me!

Why they celebrate American Thanksgiving in this city in the Netherlands

From The Smithsonian: "The story of early America— told again and again this time of year—usually goes like this: the Pilgrims took off in the Mayflower from Plymouth, England, to dock at Plymouth Rock, in 1620, in what would one day become Massachusetts. One bit that’s often skipped over is the period in which many Pilgrims lived and worked in the city of Leiden, in the Netherlands, ahead of their voyage to the new world. But in Leiden, the connection is still strong enough that every year, on the day of American Thanksgiving, people gather in a 900-year old church known as Pieterskerk to celebrate the perseverance and good fortunes of the early American settlers."

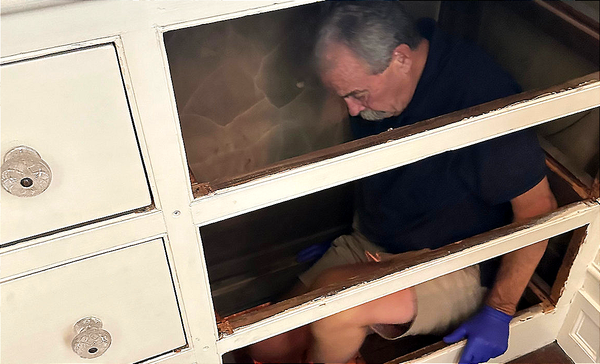

There's an almost invisible string stretching all the way around Manhattan

From the New York Post: "Being Jewish in Manhattan comes with strings attached. Orthodox Jews are allowed to push baby strollers and carry prayer books on the Jewish Sabbath thanks to a loophole made of fishing line that stretches some 18 miles on utility poles around the city. The line forms a nearly invisible enclosure, called an eruv in Hebrew. Jews are prohibited from doing these simple tasks outside on the Sabbath, but carry them out in the confines of the eruv because it symbolically turns a public space into a private one. Every Thursday, two Hasidic rabbis drive along the border of the eruv to conduct pre-dawn inspections. If they spot a break, they report it immediately to a maintenance crew that dispatches repair workers. Yearly upkeep is divided among Orthodox synagogues in Manhattan and amounts to about $100,000."

An ordinary morning on the Tokyo subway

An ordinary morning on the Tokyo subway pic.twitter.com/XB8r8bKxIY

— Out of Context Human Race (@NoContextHumans) December 1, 2024

Acknowledgements: I find a lot of these links myself, but I also get some from other newsletters that I rely on as "serendipity engines," such as The Morning News from Rosecrans Baldwin and Andrew Womack, Jodi Ettenberg's Curious About Everything, Dan Lewis's Now I Know, Robert Cottrell and Caroline Crampton's The Browser, Clive Thompson's Linkfest, Noah Brier and Colin Nagy's Why Is This Interesting, Maria Popova's The Marginalian, Sheehan Quirke AKA The Cultural Tutor, the Smithsonian magazine, and JSTOR Daily. If you come across something interesting that you think should be included here, please feel free to email me at mathew @ mathewingram dot com