How the Black Death gave rise to British pub culture

From Richard Collett for Atlas Obscura: "In the summer of 1348, the Black Death appeared on the southern shores of England. By the end of 1349, millions lay dead. According to historian Robert Tombs, author of The English and Their History, one of the many repercussions was the rise of pub culture in England. Drinking pre-Black Death was comparably amateurish. Anyone could brew up a batch of ale in their home, and standards and strengths varied wildly. Homebrewed ale was advertised with “an ale stake,” which consisted of a pole covered with some kind of foliage above the door. By the 1370s, though, the Black Death had caused a critical labor shortage. Eventually, this proved a boon for the peasantry of England, who could command higher wages for their work. As a result, households selling leftover ale were replaced by more commercialized, permanent establishments."

Why this scientist hasn't had a shower in more than fifteen years

From Dan Lewis: "As of 2019, David Whitlock hadn’t taken a bath or a shower in over 15 years. And, apparently, he doesn’t smell. Whitlock, a chemist, got his start as a never-showerer in 2003 or so when he was on a date with his future girlfriend. She — connecting with his science background — asked him what she probably thought was an innocent question: why do horses roll around in the dirt? Humans tend to avoid doing that; do horses know something we don’t? Whitlock found out that horses rub living bacteria into their skin to protect the flora living there. So he started to collect bacteria from the soil of barns, pigsties, and chicken coops, and separated out the good bacteria from the bad. Then he gathered some of these good bacteria, which neutralize dangerous organisms and hazardous substances on the skin, and made them into a spray that he uses for his daily hygiene.”

How a fight with clowns led to the birth of modern policing in Toronto

From Patrick Metzger for Torontoist: "On the night of July 12, 1855, members of the Hook and Ladder Firefighting Company descended on the house of Mary Ann Armstrong on King Street (suspected, according to newspaper stories from the day, of being a “house of ill-fame”). As Toronto’s heroes settled down to business, several men entered the bordello. The new customers were clowns from the S.B. Howes’ Star Troupe Menagerie and Circus, which was in town for a two-day engagement. When not clowning, they were roustabouts, tough characters charged with the hard physical labour of setting up and tearing down the circus. Accounts vary about what exactly happened, but all agree that a drunk fireman named Fraser either accidentally or intentionally knocked a clown's hat off. When Fraser failed to pick up the hat, a full-scale donnybrook broke out."

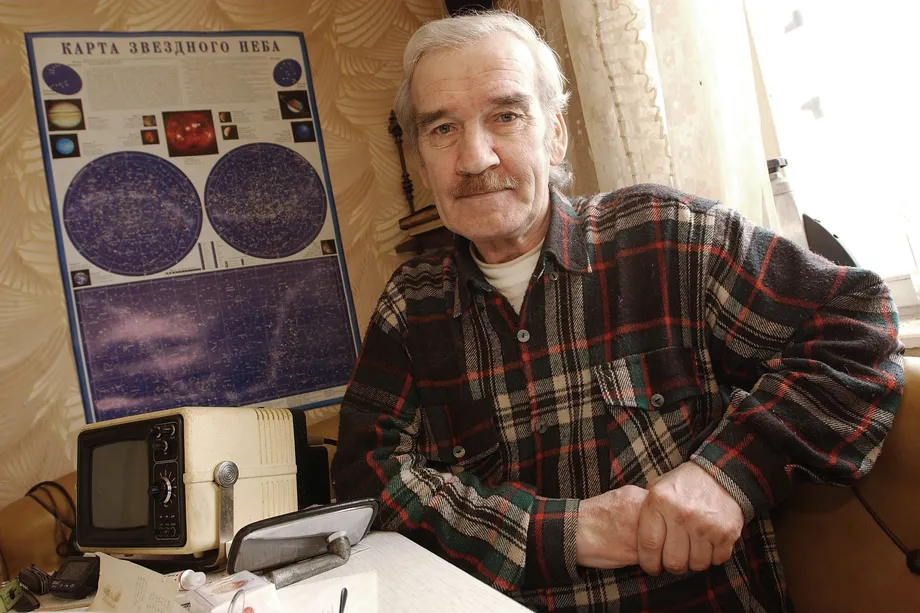

The Soviet colonel who saved the world from a nuclear holocaust

From Dylan Matthews for Vox: "On September 26, 1983, the planet came terrifyingly close to a nuclear holocaust. The Soviet Union’s missile attack early warning system displayed, in large red letters, the word “LAUNCH”; a computer screen stated to the officer on duty, Soviet Lt. Col. Stanislav Petrov, that it could say with “high reliability” that an American intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) had been launched and was headed toward the Soviet Union. First, it was just one missile, but then another, and another, until the system reported that a total of five ICBMs had been launched. Petrov had to make a decision: Would he report an incoming American strike? If he did, Soviet nuclear doctrine called for a full nuclear retaliation. But Petrov did not report the incoming strike. He and others on his staff concluded that what they were seeing was a false alarm. And it was; the system mistook the sun’s reflection off clouds for a missile."

The bizarre sociological experiment known as Biosphere Two

Steve Rose writes for The Guardian: "It sounds like a sci-fi movie, or the weirdest series of Big Brother ever. Eight volunteers wearing snazzy red jumpsuits seal themselves into a hi-tech glasshouse that’s meant to perfectly replicate Earth’s ecosystems. They end up starving, gasping for air and at each other’s throats – while the world’s media looks on. But the Biosphere 2 experiment really did happen. Running from 1991 to 1993, it is remembered as a failure, if it is remembered at all – a hubristic, pseudo-scientific experiment that was never going to accomplish its mission. However, as a new documentary Spaceship Earth shows, the escapade is a cautionary tale, now that the outside world – Biosphere 1, if you prefer – is itself coming to resemble an apocalyptic sci-fi world. Looking back, it’s amazing that Biosphere 2 even happened at all, not least because the people behind it started out as a hippy theatre group."

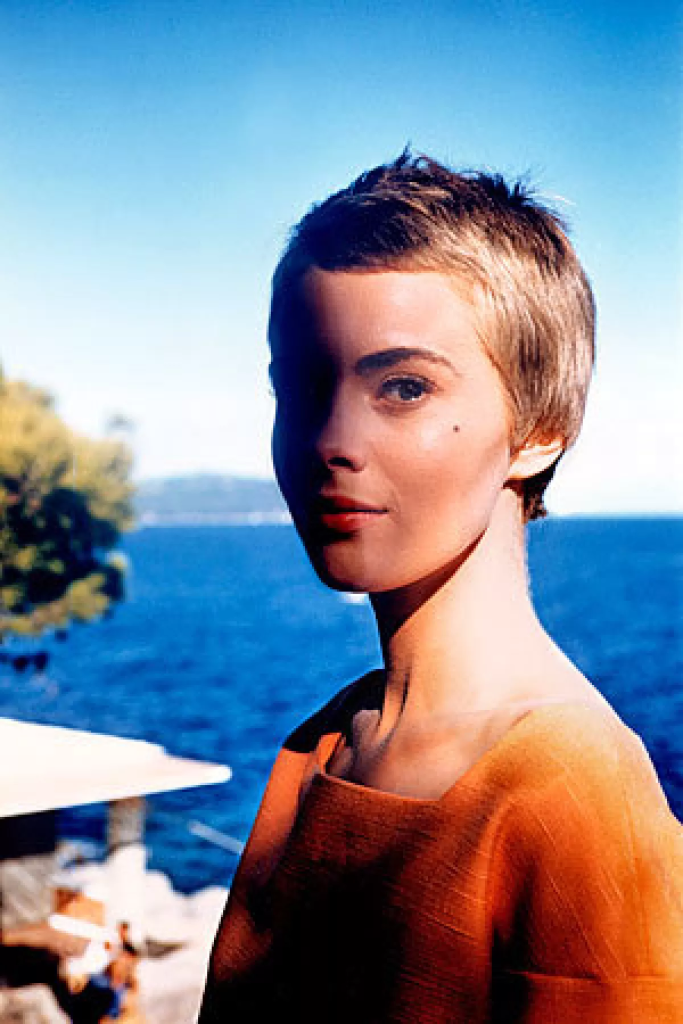

How the FBI and the Los Angeles Times destroyed a young actress’ life 50 years ago

From Nicholas Goldberg in the LA Times: "Fifty years ago, a senior editor at the Los Angeles Times came into possession of a dangerous piece of gossip, leaked to the paper by the FBI. The Times printed it without fact-checking it, and the life of a famous young actress was destroyed. The leak was malicious and the information was almost certainly wrong. It was intended by the FBI to damage the reputation of the actress, Jean Seberg, as punishment for what the bureau saw as her radical political beliefs. When Times gossip columnist Joyce Haber published the item in the spring of 1970, Seberg — the 31-year-old star of Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” and Otto Preminger’s “St. Joan,” among other films — spiraled into a long-term depression that led directly to her suicide."

Elements can be identified by the color of the flame when they are burned

Burn an element and it will show its color signature. Each element has an exactly defined line emission spectrum, we are able to identify them by the color of flame they produce

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) May 18, 2023

[read more: https://t.co/oB1lFZ2dbO]

[📹 Thoisoi: https://t.co/5dQhbNodq8]pic.twitter.com/4YkOLmnVCn