World’s oldest ultramarathon runner is racing against death

Brett Popplewell writes for The Walrus: "For fifteen years, Dag Aabye had been coming to Grande Cache, Alberta, to push his body further and faster than many of his fellow competitors, the majority of them less than half his age. Many who started the race never finished, and those who did often took up to twenty-four hours to push and drag their bodies around the 125-kilometre mud-sloped inclines and exhausting switchbacks that make up the Death Race. Dag had completed it a record seven times, each time as its oldest competitor. But now, seven long years had passed since he last crossed the finish line. And though he was markedly slower at seventy-five than he had been at sixty-nine, he refused to give up. When he ran, he did so for sport, for pleasure, and for his own survival. But there was something fleeting to it all. A general understanding that if he ever stopped running, he would stop existing altogether."

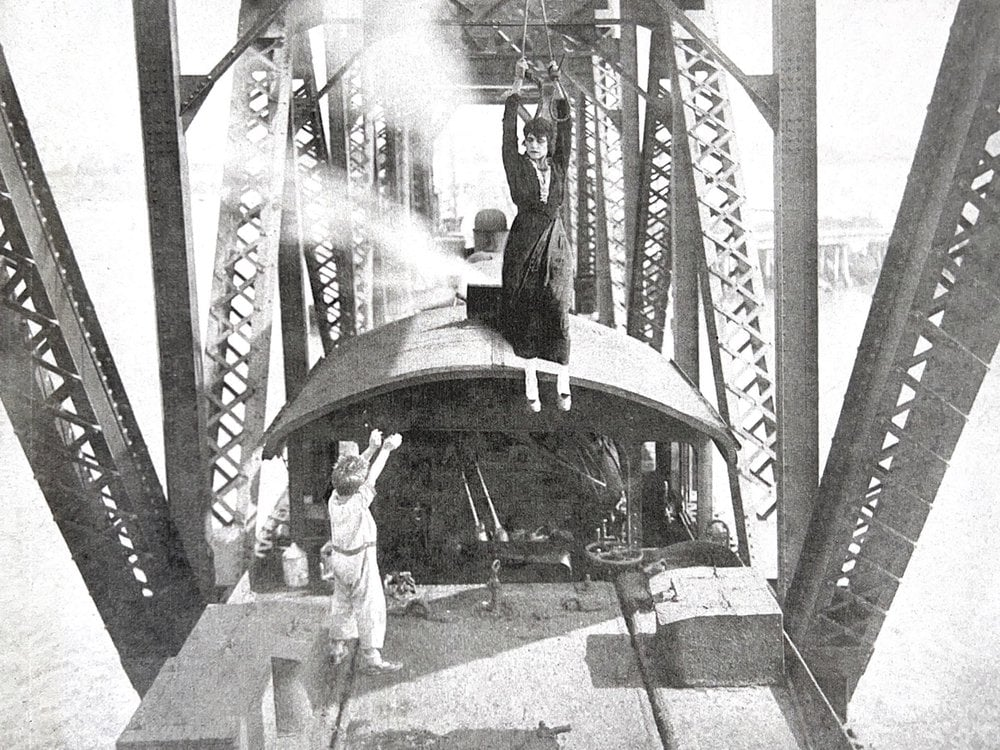

Hollywood’s first professional stuntwoman jumped from planes and trains

Elizabeth Weitzman writes for Scientific American: "Helen Gibson had a problem. She needed to leap from a standing position atop a pair of racing horses to a rope dangling from a bridge, which she would then use to swing onto a moving train engine. Once on board, she hoped to capture a gang of railroad bandits. None of these daring stunts was the issue; in fact, the entire sequence—filmed for an episode of the silent serial “The Hazards of Helen”—was Gibson’s idea. The complications arose from an anxious insurance adjuster, who flatly refused the actress coverage by declaring her an unsound risk. Few would have blamed him. It was 1916, and a significant segment of American society didn’t consider women capable of casting a vote, let alone driving a car."

The twin doctors who inspired the movie and TV series Dead Ringers

In an article originally published By New York magazine in 1975, Linda Wolfe wrote about a pair of identical twin gynecologists who died together of a barbiturate overdoses: "Like so many other people I spoke with this summer, I found myself uncharacteristically haunted by the deaths of Stewart and Cyril Marcus, the twin gynecologists found gaunt and already partially decayed in their East 63rd Street apartment amidst a litter of garbage and pharmaceuticals. Several aspects of the deaths contributed to my stupefaction. One was the very fact of the men’s twinship, the doubleness which had given them a mutual birth date and now a mutual death date as well. Another was the men’s prominence. When beggars die in a state of bizarre deterioration in New York, there are no comets seen; when two doctors still on the staff of a mighty New York hospital die in a state of bizarre deterioration, the heavens themselves blaze forth questions of responsibility. Had these men actually been seeing patients — perhaps even performing operations — while already on their route to disintegration? (Such was the case, as it turned out.)"

From glass jars all the way to the space telescope

Daniel Ganninger writes: "John Landis Mason invented the Mason Jar on November 30, 1858, and revolutionized food preservation with his new airtight jar. Mason received multiple patents on his invention starting in 1858, but twenty years later, when his patent expired, manufacturers were free to use his design. One of these manufacturing companies making Mason jars was started by five brothers in 1886. The company hit its peak during the home-canning boom in 1931, making 190 million glass jars. But the Balls wanted to diversify. In 1969, they entered the beverage can business after purchasing a business called Jeffco Manufacturing Company and then changed its name to Ball Corporation. In 1993, Ball was the third-largest producer of metal food cans and aerosol cans. While the company’s can business was thriving, the Ball Brothers Research Corporation changed its name to the Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corporation in 1995. The company delivered corrective optics to repair the Hubble space telescope."

The dead man who sued to make himself alive

Dan Lewis writes: "Donald E. Miller, Jr. was dead — he died in 1994. Nearly two decades later, very much alive, he stood in an Ohio courtroom. His goal: he wanted to not be dead anymore. Ohio probate judge Allan H. Davis had to tell him the bad news: Miller was to remain dead. The problem started nearly ten years before, when Miller ran out on his wife and two daughters, leaving them in significant debt. He disappeared — no one who knew where he went, as he never told anyone. More importantly, he never sent any child support, alimony, or other financial assistance. In 1994. Donald owed more than $25,000 in unpaid child support, money his family would certainly never see. So his (effectively) ex-wife Robin asked the state to declare him legally dead. Doing so would entitle her and the children to a Social Security death benefit of about $30,000 — money the family could really use to account for that gap. The court agreed. Donald Miller died that day — as far as the law was concerned."

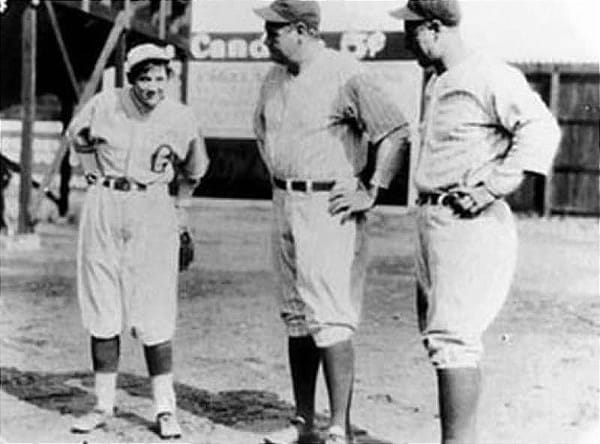

Why is New York known as The Big Apple?

Maria Popova writes: "On May 3, 1921, John J. Fitz Gerald — a sports journalist for the New York Morning Telegraph reporting on the horse-racing circuit — suddenly began referring to results from New York City as news from “the big apple.” He soon titled his entire column “Around the Big Apple,” extolling the Big Apple as “the dream of every lad that had ever thrown a leg over a thoroughbred and the goal of all horsemen.” Eventually, people began wondering why he had so nicknamed their city. Five years after he first began using the term, Fitz Gerald half-answered.Several years earlier, traveling to New Orleans for a race, he had overheard two African American stable hands discussing the horses in their respective care and where they were headed next. One of the young men told the other, in a “bright and snappy” quip, that the horse was going to “the big apple.” He died without ever saying anything else about it."

When your friend won't let you eat in peace

Just can't eat in peace! 😅 pic.twitter.com/F2dWQaTbRL

— Nature is Amazing ☘️ (@AMAZlNGNATURE) April 23, 2023