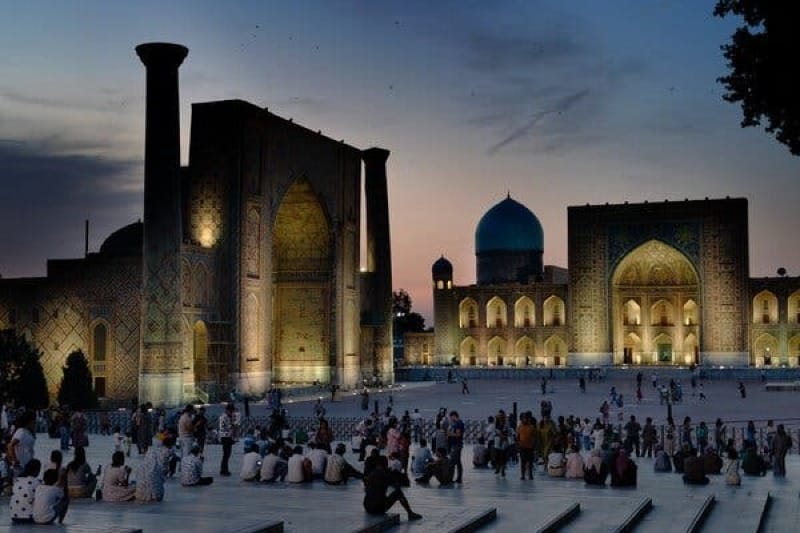

People used to visit the morgue as a form of entertainment

From JSTOR Daily: "Behind a plate-glass window, framed by grand Doric columns, repose three bodies. Except for their leather loincloths, they are naked. From a pipe above each bed, a trickle of cold water runs down their faces. Their eyes are closed. They bear the marks of their deaths: one is swollen by drowning, one gashed by an industrial accident, another stabbed. A crowd of people gathers outside the window, staring at the bodies. This is the Paris Morgue, circa 1850. Theoretically, the purpose of the display was to enlist public help in identifying unnamed corpses. But around the turn of the century, the morgue developed a reputation as a gruesome public spectacle, drawing huge crowds daily. The morgue was even listed in tourist guidebooks as one of the city’s attractions: Le Musée de la Mort. The crowds that attended the morgue attracted snack peddlers and street performers, creating an almost festival atmosphere."

The Beastie Boys paid for a punk legend to have sex reassignment surgery

From AntiMatter: "Donna Parsons said that it wasn’t until January of 2002 that she first heard the word transgender. As soon as she read about it, Donna saw herself—perhaps for the first time—and began transitioning almost immediately. Tragically, not long afterwards, Donna was diagnosed with colon cancer. She had an operation to remove the cancer that year, followed by six months of chemotherapy, but the cancer came back. “My understanding was that she was pretty much dying, and that she wanted to live out the rest of the little time she had left in the body of her choosing,” recalls Beastie Boys’ Adam Horovitz in Beastie Boys Book. “So Adam Yauch took care of it. He organized it so we gave her the money for the operation, but it was under the guise of reimbursement and unpaid back royalties for the Polly Wog Stew record from 1982. Donna got the operation, and then within a year passed away.”

How Viking-age Icelandic hunters took down the biggest animal on Earth

From Hakai magazine: "By the 13th century, Icelanders were so dependent on whales that they wrote complicated laws to establish how washed-up whales were divvied up. A whale’s size, how it died, and who owned the property where it beached all determined who got a share of the whale meat. Portioning also depended on who secured it to the shore; if an Icelander saw a dead whale floating in the sea, they were legally obligated to find a way to tether it to land. And hunters not only marked their spears with their signature emblem, they also registered those emblems with the government, improving the chances that they could claim their lawful share of any whale they speared. In addition to consuming whale meat and blubber, Norse people used the bones as tools, vessels, gaming pieces, furniture, and beams for roofs and walls."

(Editor's note: If you like this newsletter, please share it with someone else. And if you really like it, perhaps you could subscribe, or contribute something via my Patreon. Thanks for being a reader!)

The real story behind the discovery of penicillin is like a medical Manhattan Project

From PBS: "Many school children can recite the basics. Penicillin was discovered in London in September of 1928 when Dr. Alexander Fleming, the bacteriologist on duty at St. Mary’s Hospital, returned from a summer vacation in Scotland to find a mold called Penicillium notatum had contaminated his Petri dishes, and was amazed to find that the mold prevented the normal growth of the staphylococci. But there is much more to this historic sequence of events. Fleming had neither the laboratory resources nor the chemistry background to take the next giant steps of isolating the active ingredient of the penicillium mold juice. That task fell to Dr. Howard Florey, a professor of pathology at Oxford University. This landmark work began in 1938 when Florey, who had long been interested in the ways that bacteria and mold naturally kill each other, came across Fleming’s paper leafing through some back issues of The British Journal of Experimental Pathology."

Learning a foreign language changed his teenaged son's life

From the New York Times: "Over Christmas break when he was 12, Max’s curiosity led him in a new direction: He started learning Russian. I don’t know why he chose Russian, and if you ask him, he doesn’t have a good answer, either. Our family is not Russian. We don’t have any Russian friends. It’s possible that the absurdity of the pursuit was exactly what appealed to him about it. Whatever his motivation, he began practicing on a language app for an hour a day, sometimes more, and by New Year’s, he knew all the Cyrillic letters, every backward R and N. In a few weeks, he could recite simple sentences. My wife and I would walk past his room and hear him repeating Russian phrases into his iPad in a low monotone. It was like living with a 12-year-old spy. He biked to the main library downtown and took out a Russian dictionary, and then biked back a week later for a book of Russian grammar and a history of the czars."

Before telephones, guests in hotels called room service using a device called a Teleseme

From Wikipedia: "The teleseme, also known as the Herzog Teleseme, was an electric signaling device used in luxury hotels in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Guests desiring room service could use the dial mechanism of their room's teleseme to indicate a good or service from over 100 options. An attendant in a hotel office would then receive the request at a corresponding teleseme and have the order filled. Telesemes were invented by Benedict Herzog in the 1880s, but were eventually replaced with private branch exchange telephone systems. The teleseme had a dial roughly the size of a dinner plate, with written options arranged in concentric circles. The hotel guest would move the hand of the pointer to the desired service, and then would push a button which closed the circuit and alerted a hotel employee through an electrolytic annunciator."

The incredible power of this crocodile's tail

Power of the tail, salt water crocodile is airborne from a stationary position

— Science girl (@gunsnrosesgirl3) June 24, 2024

📹 tannerunderwater (Tanner Mansell)

pic.twitter.com/v1QQL6YVVo

Acknowledgements: I find a lot of these links myself, but I also get some from other newsletters that I rely on as "serendipity engines," such as The Morning News from Rosecrans Baldwin and Andrew Womack, Jodi Ettenberg's Curious About Everything, Dan Lewis's Now I Know, Robert Cottrell and Caroline Crampton's The Browser, Clive Thompson's Linkfest, Noah Brier and Colin Nagy's Why Is This Interesting, Maria Popova's The Marginalian, Sheehan Quirke AKA The Cultural Tutor, the Smithsonian magazine, and JSTOR Daily. If you come across something interesting that you think should be included here, please feel free to email me at mathew @ mathewingram dot com