The fake criminal profiler who wanted to be Sherlock Holmes

From David Gauvey Herbert in NY Mag: "In January 2010, a team of detectives and a prosecutor flew to Philadelphia to present a case to a league of elite investigators called the Vidocq Society, which met once a month to listen to the facts of cold cases. The group’s co-founder, Richard Walter, was billed as one of America’s preeminent criminal profilers. But that quickly unravelled: Since at least 1982, he has touted phony credentials and a bogus work history. He claims to have helped solve murder cases that, in reality, he had limited or no involvement with — and even one murder that may not have occurred at all. These lies did not prevent him from serving as an expert witness in trials across the country. His specialty was providing criminal profiles that neatly implicated defendants, imputing motives to them that could support harsher charges and win over juries. Convictions in at least three murder cases in which he testified have since been overturned. In 2003, a federal judge declared him a “charlatan.”

This school has no classes, no teachers and lots of freedom

Christopher Spata writes for the Tampa Bay Times: "At the Spring Valley School, three dozen students ages 5 to 18 are trusted to do what they want. There are no classes, grades or homework. There are no “teachers,” only “staff.” Students decide when it’s time to graduate. Democracy rules, and students’ voting power far outweighs that of the school’s four adults. The kids at Spring Valley can fire or hire staff, admit or expel students and spend its budget. If you call, it’s likely a 15-year-old will answer the phone. When a Tampa Bay Times reporter asked to observe a day inside the tiny private school, the students considered the request and voted to allow it. Spring Valley has doubled tours for prospective families to twice a week, and an expansion of the 2,500-square-foot schoolhouse begins this summer. Students and staff voted recently to increase tuition from $4,850 to $6,717, the first significant increase in over a decade."

Bees are sentient: inside the amazing brains of nature’s hardest workers

From Annette McGivney in The Guardian: "When Stephen Buchmann finds a wayward bee on a window inside his Tucson, Arizona, home, he goes to great lengths to capture and release it unharmed. Buchmann’s kindness – he is a pollination ecologist who has studied bees for over 40 years – is about more than just returning the insect to its desert ecosystem. It’s also because Buchmann believes that bees have complex feelings, and he’s gathered the science to prove it. This March, Buchmann released a book that unpacks just how varied and powerful a bee’s mind really is. The book, What a Bee Knows: Exploring the Thoughts, Memories and Personalities of Bees, draws from his own research and other studies to paint a remarkable picture of bee behavior and psychology. It argues that bees can demonstrate emotions resembling optimism, frustration, playfulness and fear, traits more commonly associated with mammals.

Goya’s coded love letter to the Duchess of Alba

Michael Glover writes in Hyperallergic: "How to define the astonishing allure of this great portrait by Goya? He kept it in his studio for years. In fact, as far as we know, he never parted with it. It defined him. And yet the painting feels both highly personal and strangely set apart, as if the subject possesses all the reality of a vivid human presence and all the unreality of something that can only ever be brittle and unstable, as unreachable and ungraspable as any other object of fantasy. Look at her flushed face, for example, and the drama of those arched black brows. It seems to possess all the fragility of porcelain — or an unbroken egg — and all the clarity of a dream. And her look is … what exactly? A touch sad? A touch helpless? A touch pleading? There is also a certain pride, a certain stiffness, if not haughtiness, in her stance. That face is just a tad mask-like."

Artificial intelligence and the American smile

From Jenka on Medium: "Why do you smile the way you do? A silly question, of course, since it’s only “natural” to smile the way you do, isn’t it? It’s common sense. How else would someone smile? As a person who was not born in the U.S., who immigrated here from the former Soviet Union, as I did, this question is not so simple. In 2006, as part of her Ph.D. dissertation, “The Phenomenon of the Smile in Russian, British and American Cultures,” Maria Arapova, a professor of Russian language and cross-cultural studies at Lomonosov Moscow State University, asked 130 university students from the U.S., Europe, and Russia to imagine they had just made eye contact with a stranger in a public place — at the bus stop, near an elevator, on the subway, etc."

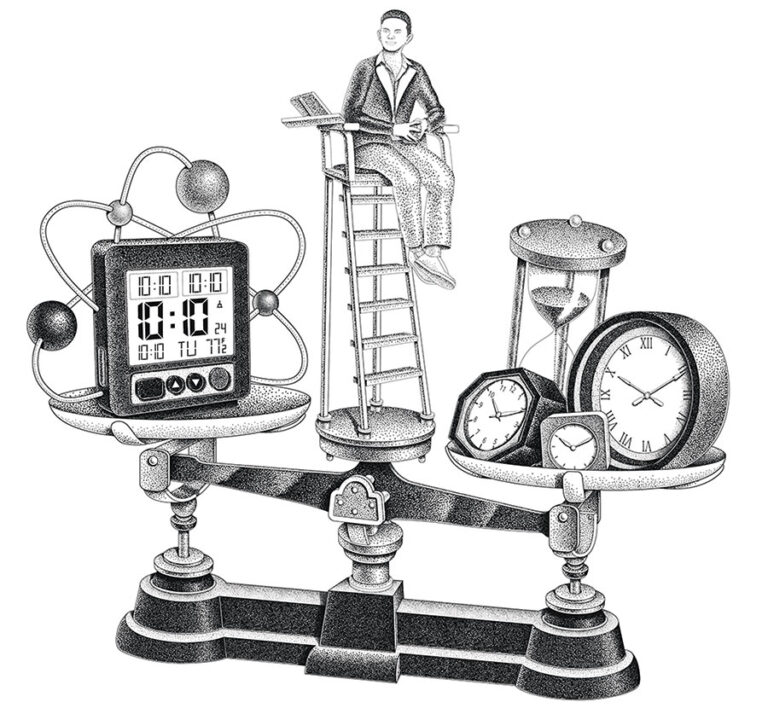

In search of lost time

Tom Vanderbilt writes in Harper's: "When I was a kid, in the touch-tone era in the Midwest, I often dialed, for no real reason, the “time lady”—an actress named Jane Barbe, it turns out—who would announce, with prim authority “at the tone,” the correct time to the second. I was, in those days, a bit obsessed with time. I would stare, transfixed, at the Foucault pendulum at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry as it swept slow traces through its day; or gawp at the patinaed green clock, topped by a scythe and hourglass-carrying temporal patriarch and marked with a single word—time—that adorned the Jewelers Building on East Wacker Drive. But nothing felt so immediate, so curiously satisfying, as having the exact time delivered through the intimacy of the phone’s earpiece. Yet it left me with a gnawing inquiry: How does she know what time it is?"

When the tables are turned

When the tables are turned.. 😂 pic.twitter.com/1gGiQ8gZ7F

— Buitengebieden (@buitengebieden) April 23, 2023