The world’s best dogsledder, and the future of the Iditarod

About two weeks after his 18th birthday, Dallas Seavey became the youngest competitor to ever finish the Iditarod; at 25, he became the youngest to win it. But his fifth victory, in 2021, carried an asterisk: He triumphed on a truncated 848-mile course, shortened to prevent the potential spread of Covid. To the sport’s critics, however, no amount of victories can erase their perception of Dallas’s wrongdoings. As he and his father came to dominate the Iditarod, they also became ensnared in a long-running debate about the very nature of dog sledding. Are huskies at their happiest running hundreds of miles a week, as mushers maintain? Or, as animal rights activists insist, are they victims of callous human ambition, sometimes required to endure unfathomable hardship? The conflict has embroiled both the Iditarod and the Seaveys in a fight that could change the sport forever—and, if some have their way, maybe even lead to its demise.

Traveling with the King of Caterpillars

David Wagner specializes in caterpillars, or, it might be more accurate to say, is consumed by them. (They are, he suggested to me, the reason he is no longer married.) Probably he knows more about the caterpillars of the U.S. than anyone else in the country, and possibly he knows more about caterpillars in general than anyone else on the planet. Wagner’s “Caterpillars of Eastern North America,” published in 2005, runs to nearly five hundred pages. It relates the life histories of roughly that many species and is considered the definitive field guide on the subject. There are roughly sixty-five hundred species of mammals, nine thousand species of amphibians, and eleven thousand species of birds. But the planet’s real diversity lies mostly beneath our regard. The largest family of beetles, the Curculionidae, contains some sixty thousand described species; another beetle family comprises twenty thousand species. It is estimated that in one family of parasitic wasps, the Ichneumonidae, there are nearly a hundred thousand species, which is more than there are of vertebrates of all kinds.

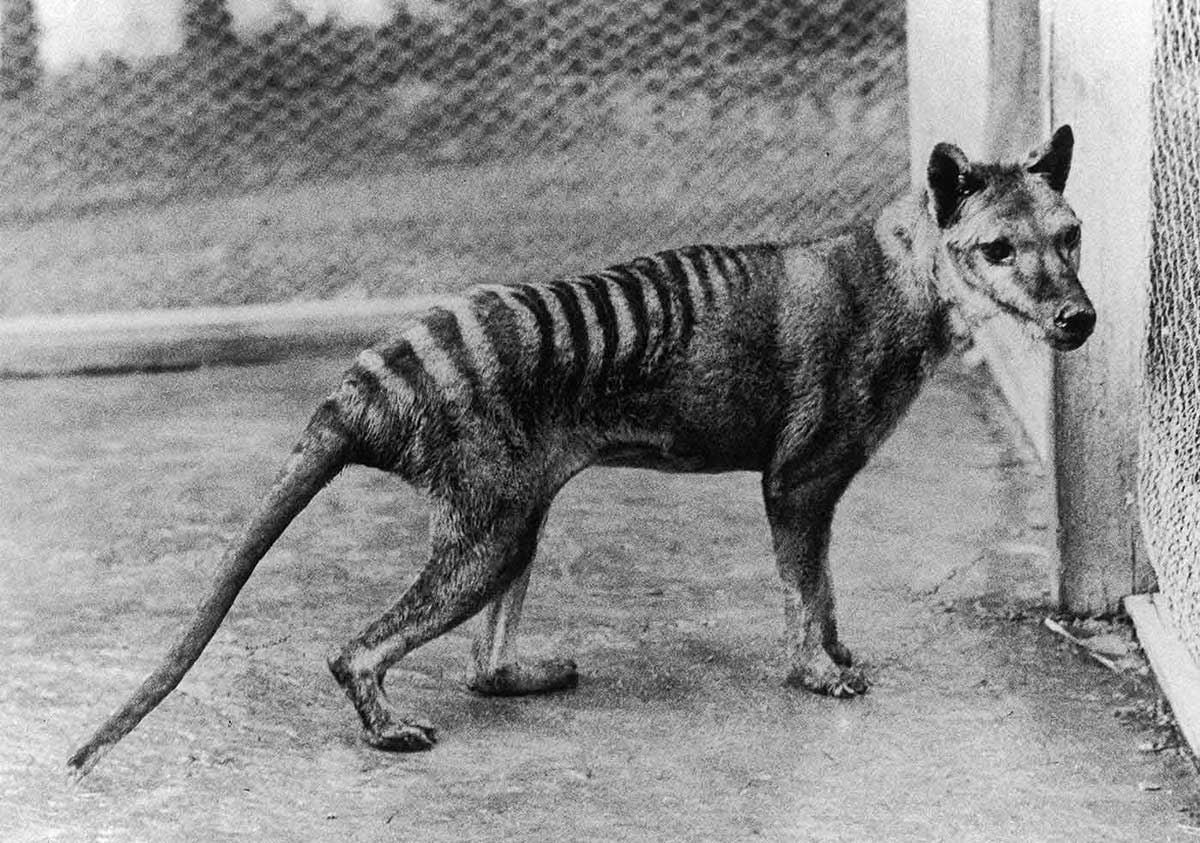

Tasmanian tiger 'probably' survived to the 1980s

On 7 September 1936, a thylacine held captive in a small Hobart zoo became the last Tasmanian tiger ever to be seen drawing a breath. Officially, at least. Reports of 'marsupial wolf' sightings in the rugged island wilderness continued well beyond the 1930s, gradually fading to whispers as the world finally came to accept the iconic native Australian creature really was gone for good. Based on the suspicious lack of verifiable observations, including prints and remains, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature closed the chapter on Tasmanian tigers in 1986. Now, a fresh investigation into a likely timeline for the last days of the thylacine has been published, confirming the species was most probably extinct before then. Led by scientists from the University of Tasmania, a team of researchers gathered an exhaustive collection of 1,237 sighting reports and developed a new method for calculating the distribution of post-bounty thylacine holdouts, finding the last individuals were gone by the 1970s.

A cult that worships superintelligent AI is looking for big tech donors

Today, much of the so-called AI we interact with excels at frivolous nonsense—generating soulless poetry, ripping off artists, cheating on homework, or gaslighting users on Bing. But a new artist collective called Theta Noir believes we should start worshiping AI now, in preparation for its inevitable role as omnipotent overlord. Theta Noirclaims that a General AI—a self-sustaining machine that has far outstripped the abilities of its creators after the “singularity”—could instead prove benevolent, ending inequalities and reorganizing our mess of a world for the better. Theta Noir hopes to meld old spiritualist traditions with the cutting edge of computer engineering—a kind of mystical materialism that, on the one hand, recognizes that machines are made by mere people, but on the other, insists that one day they’ll be something more.

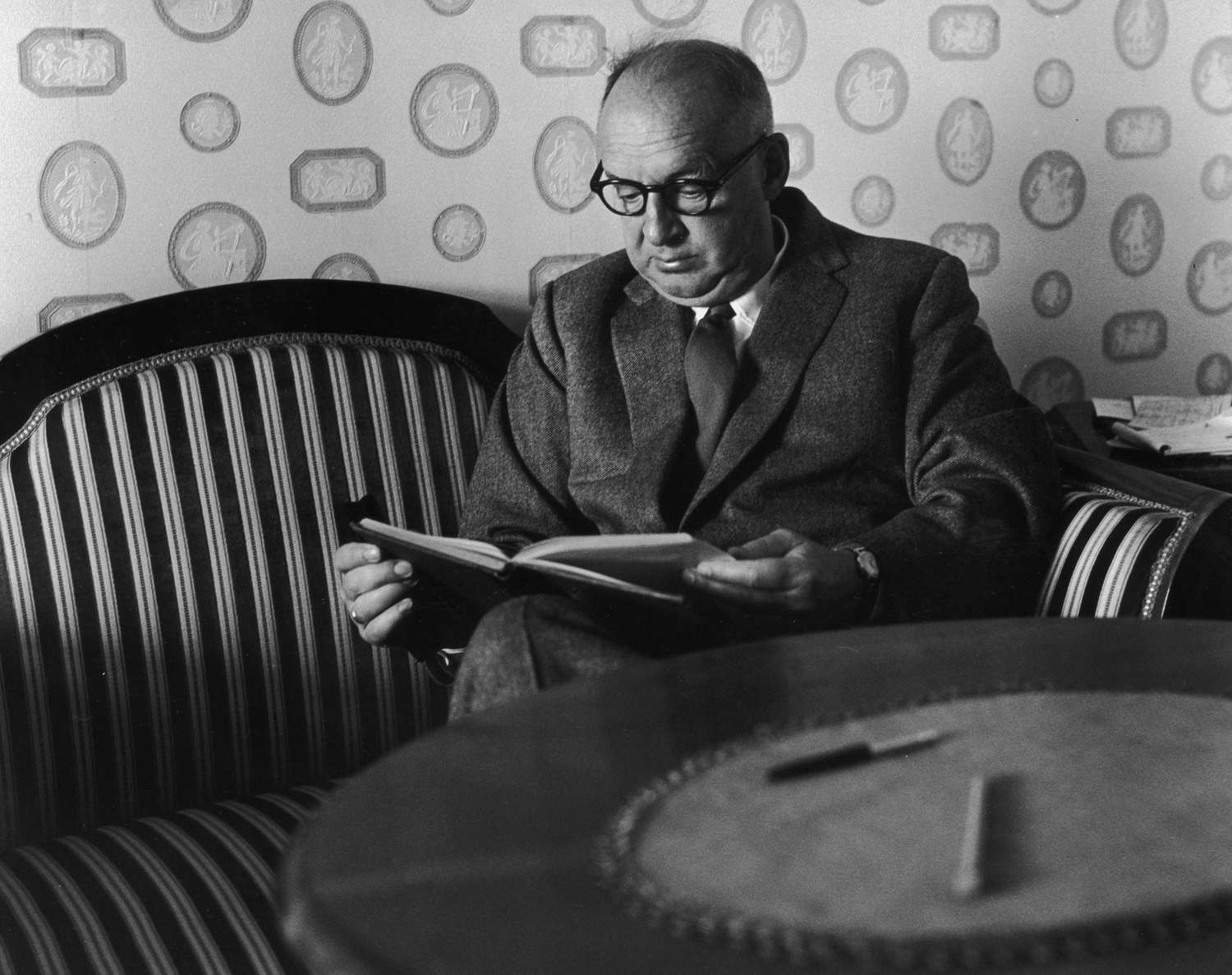

Vladimir Nabokov, butterfly illustrator

Vladimir Nabokov began collecting lepidoptera at the age of seven. Throughout a long and protean literary career, his passion for insects remained unwavering. He published his first verses as a teen-ager, shortly before the Russian Revolution; in 1918, he fled St. Petersburg for Crimea, where he surveyed nine species of Crimean moths and seventy-seven species of Crimean butterflies. Two years later, as a first-year student at Cambridge University, he described his observations in a scholarly paper for The Entomologist. In 1940, having written nine novels in Russian and one in English, Nabokov immigrated to New York, where he became an affiliate in entomology at the American Museum of Natural History. The following year, he began working at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, devoting as much as fourteen hours a day to drawing the wings and genitalia of butterflies.

America’s greatest hidden treasure was found, so why are people still looking?

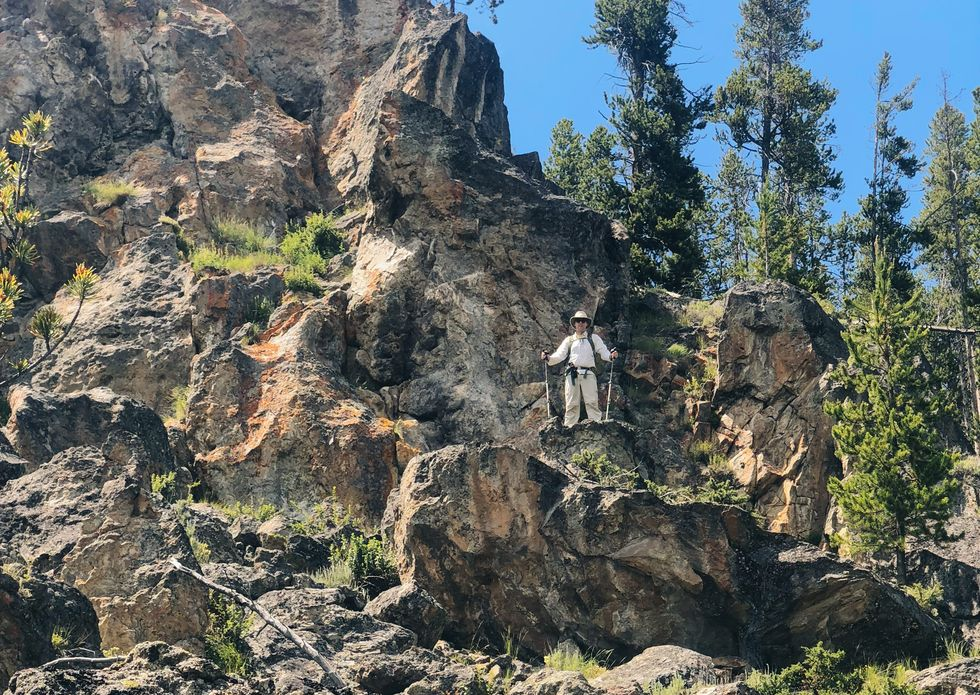

Starting in 2018, Ryan Bavetta joined thousands of other people trying to locate a bronze chest filled with gold nuggets, coins, jewelry, and other artifacts somewhere in the American West. Twice, after gathering evidence about the chest’s whereabouts from home, he flew to Salt Lake City and then drove to Yellowstone National Park to look for it. Each time he camped for a week. He drove rental cars on roads they couldn’t really handle. Then, on June 6, 2020, the incentive behind the thrilling trips to the mountains vanished. The chest was found. Still, for Bavetta and thousands of other hunters, the search wasn’t over. The chest’s location was never revealed, and the hunters began filing lawsuits and FOIA requests and analyzing photos and interviews to try to find out where it was. To this day, they’re still checking in with one another about new theories and developments that might bring them closer to understanding why the chest’s original owner started this whole thing.

Space shuttle thermal tiles and their poor conductivity

Space Shuttle thermal tiles were such poor heat conductors that you could grab them by their edges seconds after being in a 2200°C oven

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 8, 2023

[source, full video by Roscket Tasartir: https://t.co/6xTDGO1xgp]pic.twitter.com/EUbk1XqMas