The strange case of the missing James Joyce scholar

Some 16 years ago, The Boston Globe published an article about a jobless man who haunted Marsh Plaza, at the center of Boston University. The picture showed a curious figure in a long overcoat, hunched beneath a black fedora near the central sculpture. He spent his days talking with pigeons to whom he had given names: Checkers and Wingtip and Speckles. The article could have been just another human-interest story about our society’s failing commitment to mental health, except that the man crouched in conversation with the birds was John Kidd, once celebrated as the greatest James Joyce scholar alive. Kidd had been the director of the James Joyce Research Center, a suite of offices on the campus of Boston University dedicated to the study of “Ulysses,” arguably the greatest and definitely the most-obsessed-over novel of the 20th century. Armed with generous endowments and cutting-edge technology, he led a team dedicated to a single goal: producing a perfect edition of the text.

How ‘Little House on the Prairie’ built modern Conservatism

For 84 years, American kids have been growing up with Laura Ingalls Wilder’s inspiring Little House books, reading brave tales of survival on the prairies in the 19th century. The saga tells of a pioneer girl’s itinerant childhood traveling in covered wagons and starting new farms across the prairies—from Wisconsin to American Indian lands, Minnesota and Dakota Territory. She courageously helps her family fight fires, blizzards and drought; she helps bring in the cows, dress a blackbird for supper and twist hay for the cookstove. The Little House books, conceived during the Great Depression as a family project to honor the nation’s tough old pioneers, blossomed during the writing into something else. Woven into the story of Laura’s life were then-new ideas about the value of individual freedom, unfettered markets and limited government. They helped lay the groundwork for the modern libertarian strain of modern conservatism—and to an extent few people realize, they helped fund its rise.

The Croatian man who beat roulette without computers

For decades, casinos scoffed as mathematicians and physicists devised elaborate systems to take down the house in games of roulette. “It is practically impossible to predict the number that will come up,” Stephen Hawking once wrote about roulette. “Otherwise physicists would make a fortune at casinos.” The game was designed to be random; chaos, elegantly rendered in circular motion. Then an unassuming Croatian’s winning strategy forever changed the game. A manager would later say in a written statement that Niko Tosa was the most successful player he’d witnessed in 25 years on the job. No one had any idea how Tosa did it. The casino inspected a wheel he’d played at for signs of tampering and found none. When the Croatian left the casino in the early hours of March 16, he’d turned £30,000 worth of chips into a £310,000 check. His Serbian partner did even better, making £684,000 from his initial £60,000. He asked for a half-million in two checks and the rest in cash. That brought the group’s take, including from earlier sessions, to about £1.3 million. And Tosa wasn’t done. He told casino employees he planned to return the next day.

A cult leader’s missing art and the nephew obsessed with his legacy

Lester Chanin was asleep the night that the paintings were taken. He was only 15 and, though it happened over 50 years ago, he still remembers waking the next day to a world that seemed irrevocably changed. The painter, his uncle Bradford Boobis, had died hours earlier, an event Mr. Chanin described in a recent interview as like a “meteor dropping out of space.” Then the paintings disappeared. “It blew the family up,” Mr. Chanin said. There’s a good chance you’ve never heard of Bradford Boobis. A tall man whose chiseled face was framed by a fluffed pompadour, Boobis was, to all appearances, a colorful eccentric and minor celebrity. But to his family and followers, he was a towering figure — the sun around which the family orbited, according to Mr. Chanin. Boobis had also, in his later life, started courting followers to a cultlike philosophical movement which he called Life, Infinity, Man.

How Alberta became the first place in the world to banish the rat

The rest of the world is frequently surprised to discover that in humanity’s centuries-long battle with the rat, there has been only one indisputable victor: The four million people of the Canadian province of Alberta. “Norway rats are one of the most destructive creatures known to man,” reads the official Alberta government write-up on its world-renowned rat control program. “The people of Alberta are extremely fortunate not to have rats in the province.” For nearly 70 years, Alberta has successfully kept rats from taking hold of an area larger than France — and it has done so by waging a vigilant and all-out war on the rodent. “Because rat invasion is threatening Alberta, we need to be properly organized and know what to do, in order to fight the battle successfully,” reads a 1954 government booklet, Rat Control in Alberta, that was distributed with virtual ubiquity in the province’s public places.

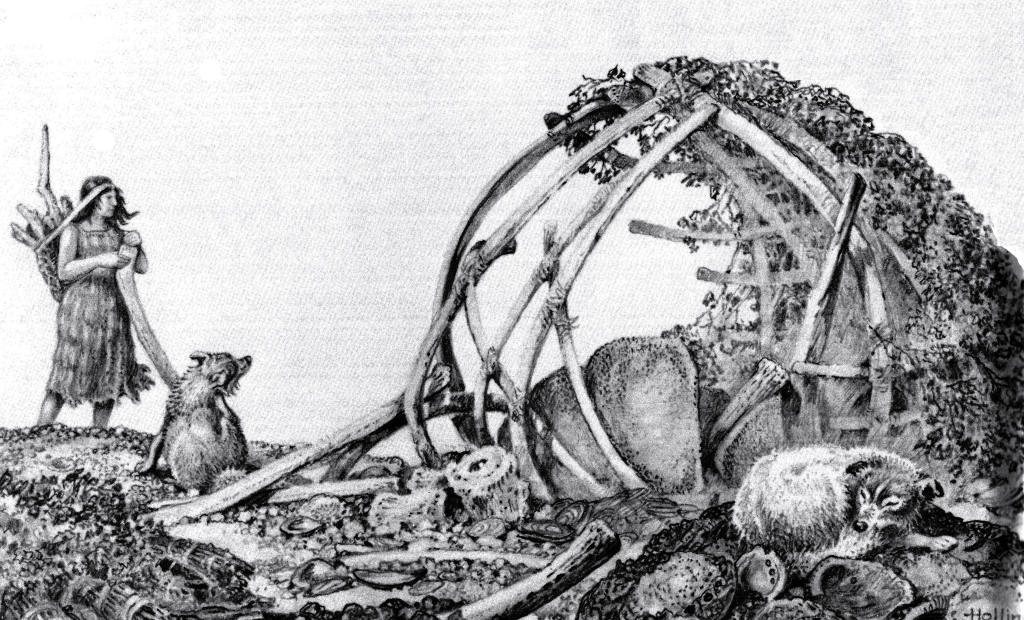

Stranded on the Island of the Blue Dolphins: The true story of Juana Maria

San Nicolas Island, part of the archipelago of the Channel Islands off the California coast, is windswept and largely barren, so much so that the U.S. Navy considered it a candidate location for the first tests of the nuclear bomb. To some, it is known as the Island of the Blue Dolphins. In 1853, men discovered a woman on San Nicolas inside a hut made of whalebones and brush. She was wearing a dress made of cormorant feathers sewn together with sinew. She said she had been on the island by herself for 18 years. But recently, researchers have shown that nearly every facet of the woman's story—a story accepted for more than a century—was wrong. She was not the last of the Nicoleños; her people did not flee the island, she was able to communicate with other Native Californians; and, most intriguingly, she was not alone on San Nicolas at all. She voluntarily stayed on the island after her son refused to board the departing ship.

How a giant wave can sneak up on you

A sneaker wave is a disproportionately large coastal wave that can appear in a wave train without warning. This video was shared by Marcella Ogata-Day to help bring awareness of the dangers of sneaker waves

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 10, 2023

[source, read more: https://t.co/goar0ni9xu]pic.twitter.com/YBNQ2z6wsF