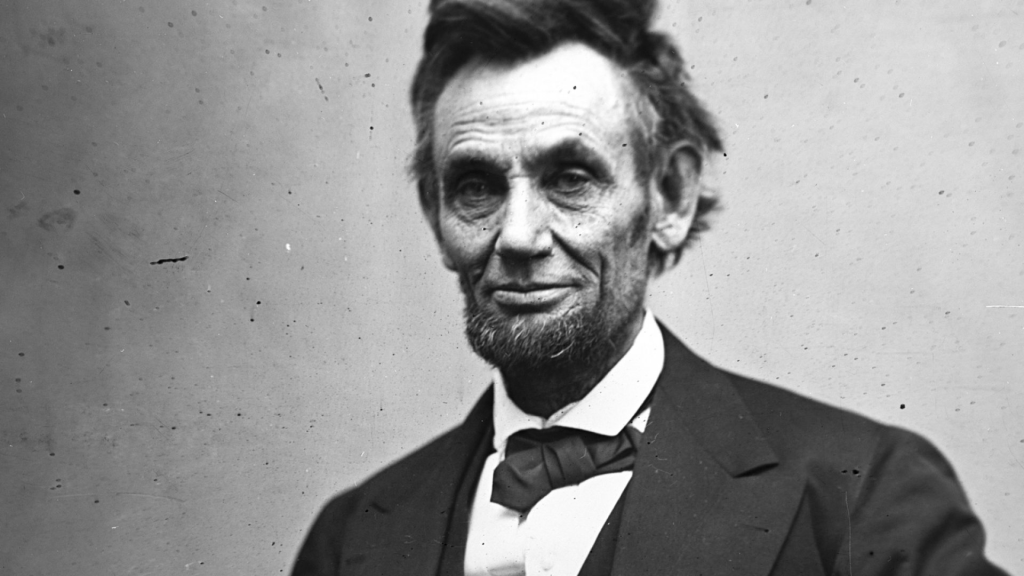

The secret plot to hold Abraham Lincoln’s dead body for ransom

In the 1800s, counterfeiting became extremely common, and the one person acknowledged as America’s greatest counterfeiter was Benjamin Boyd. Boyd used to work for a Chicago syndicate run by James “Big Jim” Kinealy. However, Abraham Lincoln’s legislation to arrest counterfeiters resulted in Boyd being sentenced to prison in 1876. With Big Jim’s top man gone, his business was in a wrecked state. He had to do something to get Boyd freed from prison. Out of the blue, a bizarre plan arose: steal Abraham Lincoln’s body, bury it in the Indiana dunes, and then ask for $200,000 for ransom along with the pardon and freedom of Benjamin Boyd. To execute this plan, Kinealy hired a bartender, Terrence Mullen, and a counterfeiter, Jack Hughes. The two decided to pull off the heist on election night when no one was in town. There was also very minimal security at Lincoln’s grave, which meant the chances for the plan to go wrong were significantly less.

Why did the US government amass a billion pounds of cheese?

The year was 1981, and President Ronald Reagan had a cheese problem. Specifically, the federal government had 560 million pounds of cheese, most of it stored in vast subterranean storage facilities. Decades of propping up the dairy industry—by buying up surplus milk and turning it into processed commodity cheese—had backfired, hard. The Washington Post reported that the interest and storage costs for all that dairy was costing around $1 million a day. “We’ve looked and looked at ways to deal with this, but the distribution problems are incredible,” a USDA official was quoted as saying. “Probably the cheapest and most practical thing would be to dump it in the ocean.” Instead, they decided to jettison 30 million pounds of it into welfare programs and school lunches through the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program. But the surplus was growing so fast that 30 million pounds barely made a dent. By 1984, the U.S. storage facilities contained 1.2 billion pounds, or roughly five pounds of cheese for every American.

America’s first plane bomber, and his intended victim

As Daisie prepared for a trip to Anchorage, Jack hatched a new plan. A plan that would remove from his life the two things that he believed were keeping him down—a lack of money, and his mother—no matter the cost. After buying the requisite equipment, Jack sat down in the basement of his home and got to work. He assembled twenty-five sticks of dynamite, a timing device, an Eveready six-volt “Hot Shot” battery and two dynamite caps into a compact time bomb. He wrapped the bomb up, packed it inside Daisie’s heavy Samsonite suitcase, and loaded the case into the trunk of her Chevrolet sedan. Then Jack and Gloria drove Daisie to the airport. It was November 1, 1955. After saying goodbye to Daisie at the gate, Jack and Gloria stopped for a snack at the airport coffee shop—but not before Jack bought an insurance policy on Daisie’s life from a vending machine at the terminal, a common practice in a time marked by frequent air crashes.

Andy Baio on what it's like to be colorblind

For some people, colorblindness is a serious liability that closes doors on career dreams. It’s hard to become a pilot, train conductor, or pathologist if you can’t differentiate colors in critical instruments, signals, or tissue samples. For others, it seriously impacts their day-to-day ability to do their jobs, like surveyors spotting flags, doctors looking at skin conditions, or electricians looking for colored wires. But for me, it’s just a lifelong series of unnecessarily confusing interactions, demonstrating that the world wasn’t designed for people like me. There are an estimated 350 million colorblind people in the world. About 8 percent of men, roughly 1 in 12, have some form of color vision deficiency. My mom’s color vision is even worse than mine, which is very unusual: only about 0.5 percent of women globally are colorblind, about 1 in 200. I’ve had a lot of conversations about my colorblindness with people who aren’t colorblind. (Pro tip: when you meet a colorblind person, don’t repeatedly point to things and ask what color they are.) It seems like the very idea of colorblindness is hard for them to visualize.

The Nazi scientists behind America's aerospace dominance

Long before the fall of Berlin at the end of World War II, American military intelligence had begun planning to steal advanced Nazi technology. The German state was renowned for its technological prowess, and its propaganda extolled the country’s development of “wonder weapons” like the V-2 missile and ME-262 jet fighter. The Americans intended to obtain this technology with the goal of developing a military advantage over Japan, which could speed along a victory in the Pacific. There were two major components to the American’s efforts: the Field Information Agency Technical (FIAT), which centered around agents capturing technical data from research sites across Germany, and Operation Overcast, which involved hunting down and capturing the most important members of the Nazi scientific establishment. Operation Overcast’s targeting was guided by the so-called Osenberg List, a Gestapo document which, on Hitler’s orders, cataloged the most important scientists and engineers to the Nazi war effort. A copy of the document had been insufficiently flushed down a toilet at Bonn University.

What it's like to drive a tractor-trailer as a single mother

In Indiana, a few hours south of the facility where Jess had driven her first truck, cornfields gave way to lone motels and fast-food chains. “What’s more American than gas stations and strip malls?” Jess asked. Flecks of rain spattered the windshield, and the sky ahead was fearsome gray. Glancing off the road for a few seconds at a time, Jess scrolled her phone for tornado warnings. Did I know, she asked, that breweries and soda companies halt all other production to bottle water during national emergencies? Also: Drivers who ship the syrup for Coca-Cola need a HAZMAT license because it contains flammable material. For a few years, Jess shipped mostly produce, which gave her unique and disturbing insight into our nation’s food systems. “These apples,” she said, showing me one she’d had in her truck for two weeks, “are last year’s apples. The onions you buy in a grocery store have been in a warehouse for a year.” Bananas are stored at 56 degrees if they’re green, 57 if they’re yellow. Don’t ask about the chicken in fast food.

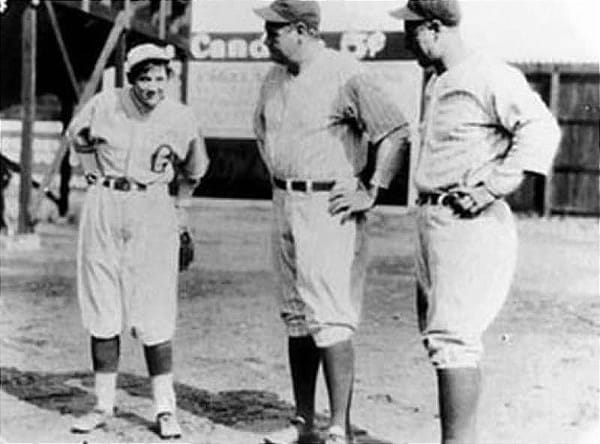

Buster Keaton's most amazing stunts

Some of Buster Keaton's most amazing stunts

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 14, 2023

[full video, HD, Don McHoull: https://t.co/0O13dVd2yO]pic.twitter.com/4pnhsJpplH