The poet who invented social media in the 18th century

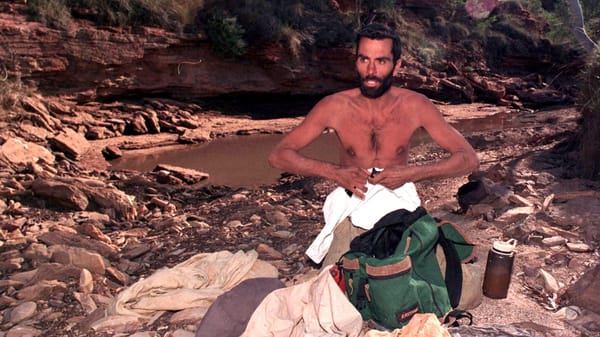

In 1747, the young poet Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim was sitting in his study in the small German town of Halberstadt, surrounded by stacks of letters from his friends and associates, and had an epiphany. He realized that despite having corresponded with so many people, he had never actually met most of them in person. And this got him thinking: what if there was a way to visualize all the people he had formed relationships with through letter writing? And thus, the poet’s Temple of Friendship was born. Gleim set out to collect painted portraits of all his friends and relatives, creating an extensive personal portrait gallery that soon filled all the walls of his apartment. He referred to this portrait gallery as his Tempel der Freundschaft (“Temple of Friendship”). He carefully thought about the arrangement of his portrait gallery: his own portrait was always at the center of the gallery, while other portraits were positioned around it.

Jean Denis and the “Transfusion Affair”

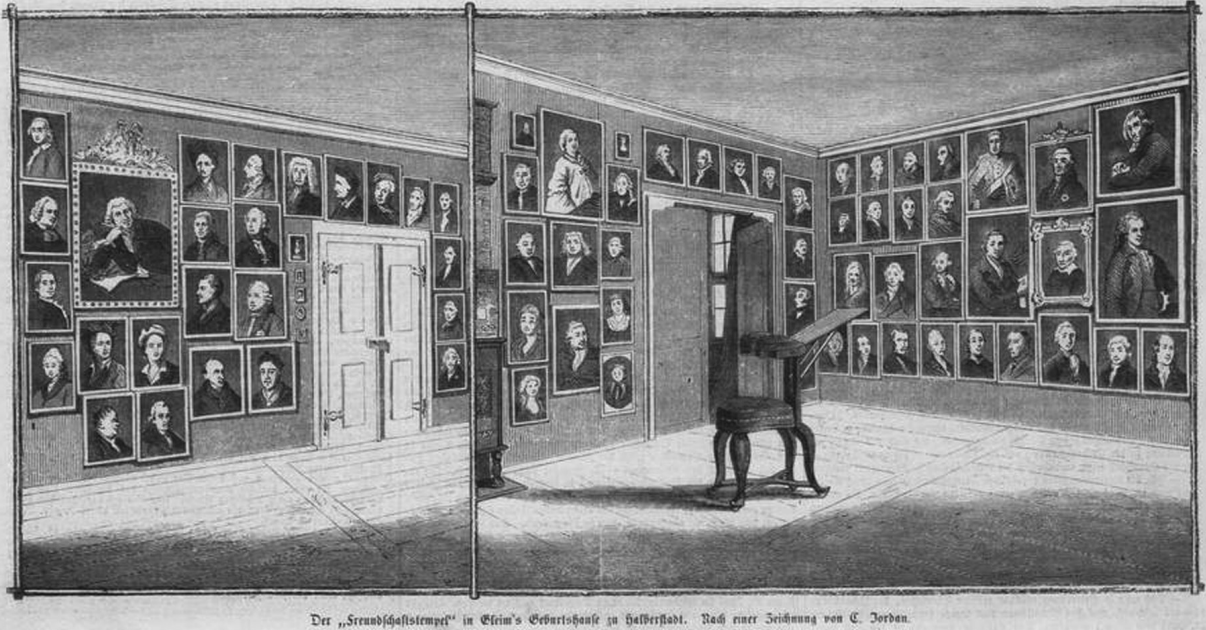

Beginning in the spring of 1667, public opinion in Paris was rocked by a remarkable affair involving domesticated animals: the first practical experiments to transfuse animal blood into humans for therapeutic purposes. The experiments that came to be known as the “Transfusion Affair” were shrouded in the competing claims of a highly public controversy in which consensus and truth, alongside the animal subjects themselves, were the first victims. “There was never anything that divided opinion as much as we presently witness with the transfusions”, wrote the Parisian lawyer at Parlement, Louis de Basril, late in the affair, in February 1668. “It is a topic of the salons, an amusement at the court, the subject of philosophical dissertations; and doctors talk incessantly about it in all their consultations.” At the center of the controversy was the young Montpellier physician and “most able Cartesian philosopher” Jean Denis, who experimented with animal blood to cure sickness, especially madness, and to prolong life.

For insect detectives, the trickiest cases involve the bugs that aren’t really there

Gale Ridge could tell something was wrong as soon as the man walked into her office at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. He was smartly dressed in a collared shirt and slacks, but his skin didn’t look right: It was bright pink, almost purple — and weirdly glassy. Without making eye contact, he sat hunched in the chair across from Ridge and began to speak. He was an internationally renowned physician and researcher. He had taught 20 years’ worth of students, treating patients all the while, and had solved mysteries about the body’s chemistry and how it could be broken by disease. But now, he said he was having serious health issues he didn’t know how to deal with. “He was being eaten alive by insects,” Ridge, an entomologist, recalled recently. “He described these flying entities that were coming at him at night and burrowing into his skin.” The biggest problem, however, was that the bugs didn't exist.

Vikki Dougan, the 1950's starlet who may have inspired Jessica Rabbit

In the late '50s, Vikki Dougan and her backless dresses became tabloid fodder for Hollywood gossip columns — and inspired a profuse number of groan-inducing puns. In a March 29, 1957 Hollywood Today column headlined “Vikki Dougan … Backs Into a Film Career,” Erskine Johnson suggested that Ms. Dougan’s dresses are “lower in the back than a teenager’s hot rod.” But after a whirlwind year of public appearances and seemingly nonstop press, interest in Ms. Dougan’s fetching backside waned. The starlet seemed to disappear from Hollywood as quickly as she had arrived. Online biographical information on Ms. Dougan is scant, unlike the pages and pages devoted to Natalie Wood, Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor. There’s a wan IMDB page, and a number of blog posts citing conflicting information about her life. And while Ms. Dougan’s rise to fame is well documented, there is little explanation of where she went.

Are the Great Lakes actually inland seas?

The Great Lakes of North America’s midsection—Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario—together span nearly 100,000 square miles, with a combined coastline just shy of 10,000 miles. They hold more than a fifth of Earth’s unfrozen fresh water, straddle an international border, and help move more than $15 billion dollars worth of cargo each year. They even have their own U.S. Coast Guard district, the only lakes with such a distinction. So should we really be calling them the Great Inland Seas? “The most accurate answer you’re going to get is, ‘I don’t know,’” says John Richard Saylor, author of the upcoming Lakes: Their Birth, Life, and Death. “I do think it comes down to semantics, what you want to call a ‘sea.’” For many, the Great Lakes are indeed greater than lakes. The United States Environmental Protection Agency, for example, describes them as “vast inland freshwater seas.” A seminal 2017 paper in Limnology and Oceanography, authored by some of the most influential researchers studying the lakes, also refers to them as ‘inland seas.’ But what makes a sea varies by source.

Brandon Sanderson makes $10M a year with his writing, but you've probably never heard of him

Most years, Brandon Sanderson makes about $10 million. Last year, he made $55 million. This is obviously a lot of money for anyone. For a writer of young-adult-ish, never-ending, speed-written fantasy books, it’s huge. By Sanderson’s estimation, he’s the highest-selling author of epic fantasy in the world. In five months, Sanderson published two books. During the Covid lockdowns, he wrote and/or edited seven: two for his regular publisher, a graphic novel, and four more in secret, telling no one but his wife until he surprise-announced a Kickstarter in March 2022 to crowdfund their publication. (He raised $42 million in a month, by far the most successful Kickstarter ever.) Since his debut, Elantris, in 2005, Sanderson has published 30-plus books, the biggest ones in excess of 400,000 words; there are far more if you count the novellas.

Beluga whale returns a phone someone dropped

That time a beluga whale returned a phone someone dropped in the sea waters of Norway

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 2, 2023

[full story: https://t.co/Qgx9yM0Pow]

[about the beluga: https://t.co/8bnwtYRuGO]pic.twitter.com/VQkKW1UfsT