The man who stole the Mona Lisa and took it back to Italy

Saturday was the anniversary of the birth of the Italian painter who made perhaps the biggest art repatriation blunder in history. In 1911, Vincenzo Peruggia stole da Vinci’s masterpiece from Paris and later brought it to Florence. But the theft’s success as a repatriation effort was very short-lived. Less than three years after it was stolen from the Louvre, the Mona Lisa returned to Paris in January 1914. Though he was misguided as a historian and an umpire of provenance — the painting had been clearly and cleanly purchased by the King of France, the country to which it was ultimately returned — Peruggia’s caper is worth recalling at a time when repatriation remains a murky battleground.

The scandal that rocked a Cleveland fishing tournament

There’s nibble-around-the-edges, cut-the-corners cheating, like going five miles an hour over the speed limit or faking sick to get out of work. This is a story about the other kind: whole-hog, all-in cheating where plausible deniability doesn’t exist. It begins in Cleveland’s Gordon Park, on the shores of Lake Erie, where the Lake Erie Walleye Trail was wrapping up its championship event on Saturday. Fischer weighed the fish of angler after angler, picking up their fish and setting them on a scale. Late in the proceedings, the anglers of boat No. 12, Chase Cominsky and Jake Runyan, brought their five-fish catch up for weighing. They needed to beat 16.89 total pounds to claim Team of the Year honors and $30,000 in various prizes. Their catch’s weight: 33.91 pounds. The silence that greeted Fischer’s announcement was the first sign that something was very much amiss.

Loie Fuller and her legendary Serpentine Dance

With her "serpentine dance" — a show of swirling silk and rainbow lights — Loie Fuller became one of the most celebrated dancers of the fin de siècle. On November 5, 1892, she premiered at the Folies, a venue known at the time for its strippers, gymnasts, and trapeze artists. Swathed in a vast costume of billowing white Chinese silk, Fuller began her performance. Using rods sewn inside her sleeves, she shaped the fabric into gigantic, swirling sculptures that floated over her head. The audience saw not a woman, but a giant violet, a butterfly, a slithering snake, and a white ocean wave. After forty-five minutes, the last shape melted to the floorboards, and the stage went black. When the lights went back on, Fuller reappeared to thunderous applause.

Mike Conner v. The Pain

Mike Conner sits in his truck atop a hill in Boring, Oregon, where he can feel the summer breeze through the window and see the sun at its meridian over the fields and the snowcapped tip of a distant Mount Hood poking into a cloud-dotted sky. He sits here and thinks about cutting off his feet. His legs are barely his anymore—just fused cadaver bone and metal. Nearly half of six-foot-four, 225-pound Mike is steel and titanium: the majority of his legs from his knees down, his shoulder, his elbow, his wrist, his back, and his spine. In the life that came before the pain, Mike was an engineer. On April 2, 2013 he was working at Northside Church in Clovis, California, checking sprinklers. The job was four flights up, in the attic, with nothing but steel beams and a catwalk suspended over the altar. He went to step across the beam, and then he fell.

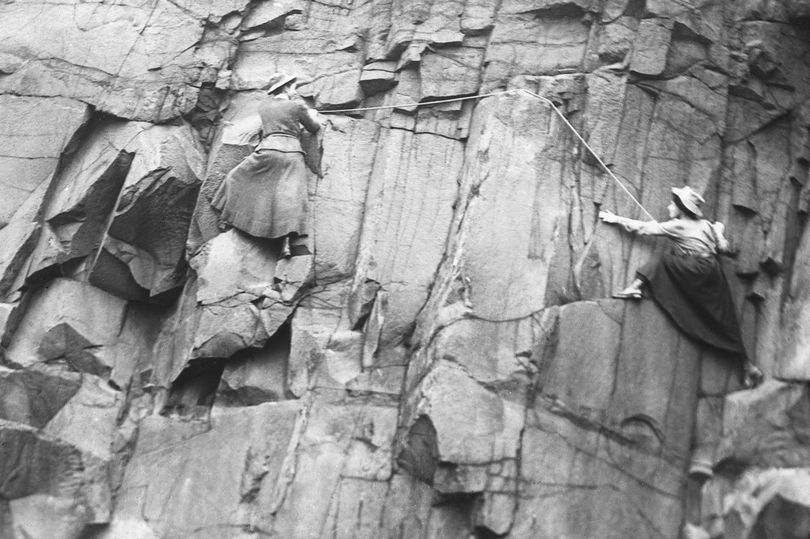

These women climbed Scottish mountains in dresses, hats, blouses and sensible shoes

These days, rock climbing equipment is high tech, with safety features like harnesses, spring-loaded carabiners, helmets, as well as special climbing shoes with crips, spikes and rubber soles. But in the 1900s, Lucy Smith and Pauline Ranken, two members of the Ladies' Scottish Climbing Club founded in 1908, ascended mountains like the Salisbury Crags wearing long, ankle-length skirts, hats, blouses and smart shoes. The only protection they had was a length of rope that was tied around each of their waists. There were no harnesses, crampons or other modern safety equipment available to them at the time.

The 1925 cave rescue that captivated the nation

Floyd Collins traipsed over damp leaves and thawing snow and stepped into the shadow of a cave. It was an unusually warm Kentucky winter morning—January 30, 1925—and a thick curtain of icicles hung from the lip of the cavern like the pipes of a church organ. The cave's mouth, a bow-shaped rock overhang that resembled a band shell, dripped with water. Collins paid it no attention. This was a normal day at the office. For weeks, the 37-year-old cave explorer had spent up to 12 hours every day clearing gravel, sandstone, and limestone from the narrow passageway winding below his feet, and today was no different. Collins removed his coat and hung it over a nearby boulder. He fiddled with his kerosene lamp and slung a rope over his shoulder. Then he dropped into a manhole-sized cavity. When Floyd Collins emerged, he'd be one of the most famous people in the world.

This plant can control a robot arm

Living plant controls a machete through an industrial robot arm pic.twitter.com/jQYzMzoG0W

— Canneo (@canneo2103145) October 4, 2022