The giant "acoustic mirrors" that once protected Britain

If you're driving through Britain, you might see giant concrete blocks with concave openings. What are they? Acoustic mirrors. More than 100 years ago, these mirrors were built along the coast of England, with the intention of using them to detect the sound of approaching German zeppelins. Invented by William Sansome Tucker, and operated at differing scales between around 1915 and 1935, the acoustic mirrors were able to signal an aircraft from up to 24 kilometers away, giving enough time to allow British defence to prepare for counterattack. The concave structures responded to sound by focusing the waves to a single point, where a microphone was positioned. Not only were they able to announce the arrival of an aircraft, but they could also determine the direction of attack of the plane to an accuracy of 1.5 degrees. Their development continued until the mid-1930s, when the invention of radar made them obsolete.

This internet service provider's security keys are generated by a wall of lava lamps

You might think that the best security keys would be generated by computers, but in the case of CloudFlare, which caches and distributes data for thousands of large companies, you would only be half right. Computers, being logical devices, struggle with generating randomness, so CloudFlare uses real objects to generate "entropy," which in cryptography means unpredictability. Encryption keys need to be unpredictable, or else an attacker can try to detect patterns. That's where lava lamps come in, because they're an inherently random variable. CloudFlare has two other randomness generators that are being built: The first, in the company's London office, is known as the "Chaotic Pendulums," and features giant grandfather-clock style pendulums, and the second, under construction in the company's Austin office, is called "Suspended Rainbows." Entropy is generated via patterns of light that are projected on walls, the ceiling, and the floor.

Publishers gave away more than 120 million books during World War II

In 1943, in the middle of the Second World War, America's book publishers took an audacious gamble. They decided to sell the armed forces cheap paperbacks, shipped to units scattered around the globe. Instead of printing only the books soldiers and sailors actually wanted to read, though, publishers decided to send them the best they had to offer. Over the next four years, publishers gave away 122,951,031 copies of their most valuable titles. "Some of the publishers think that their business is going to be ruined," the prominent broadcaster H. V. Kaltenborn told his audience in 1944. "But I make this prediction. America's publishers have cooperated in an experiment that will for the first time make us a nation of book readers." He was absolutely right. From small Pacific islands to sprawling European depots, soldiers discovered the addictive delights of good books. By giving away the best it had to offer, the publishing industry created a vastly larger market for its wares. More importantly, it also democratized the pleasures of reading, making literature, poetry, and history available to all.

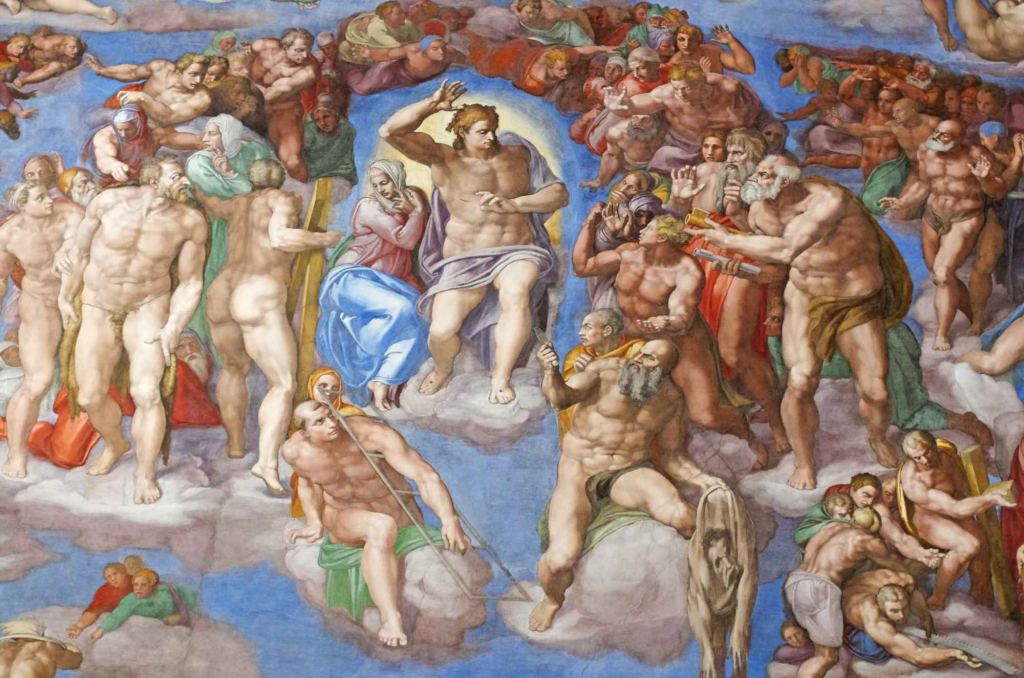

Michelangelo's "The Last Judgment" was hugely controversial at the time

A thread from Sheehan Quirke, otherwise known as The Cultural Tutor: "Pope Clement VII asked Michelangelo In 1533 to return to the Sistine Chapel and paint on the wall behind its altar a depiction of the Last Judgment as prophesied in the Bible. Michelangelo's style was often contrasted with Raphael, one of the other defining artists of the High Renaissance. For whereas Raphael was graceful, harmonious, and ever appropriate, Michelangelo could be turbulent, forceful, improper, and violent. Michelangelo diverged from tradition in several important ways, not least by departing from the Biblical account of the Last Judgment. For example, he did not paint Jesus seated on a throne. Jesus hadn't been portrayed as beardless for centuries (which was controversial in itself) notwithstanding that his heavily muscled body makes him look like a Greek god. This was highly unorthodox. Also, the fact that most of the bodies in the painting were naked fell foul of the Council of Trent's decree. In the year of Michelangelo's death, 1564, his former pupil Daniele da Volterra was hired to paint loincloths over the naked figures."

Why are pencils almost always yellow?

The yellow pencil has been an affordable writing tool for over 125 years. It is estimated that they represent 2/3 of all pencils sold in North America. So why is yellow such a popular colour? At the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, the world was introduced to the Koh-i-Noor 1500 – a wooden pencil manufactured in what is now the Czech Republic. But this was no ordinary pencil. After being covered in fourteen coats of vivid yellow paint, it was dipped in 14-carat gold. The Koh-i-Noor 1500 became somewhat of a sensation in Paris. This newfangled pencil contained the highest quality graphite available, which, at the time, came from China. Yellow is one of China’s imperial colours, representing royalty, power and prosperity. The next world’s fair took place in Chicago in 1893. It was here, at the World’s Columbian Exposition, that the unique yellow pencil made its American debut. The public immediately took a shine to the product. Before long, manufacturers started painting their pencils yellow to compete with the popularity of the Koh-i-Noor 1500.

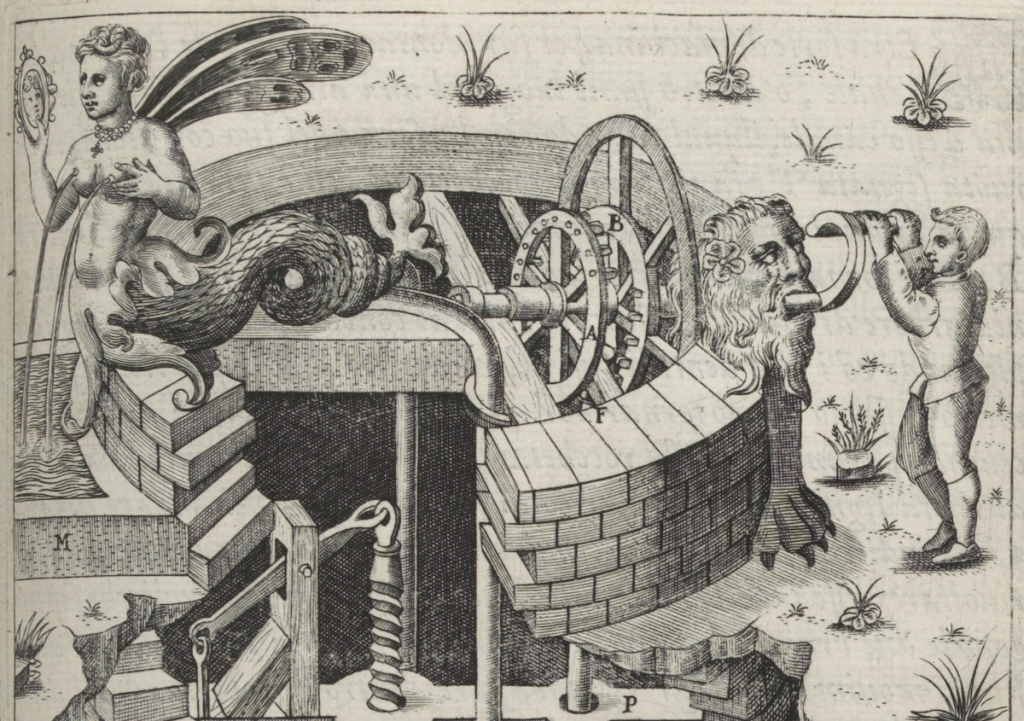

Agostino Ramelli’s Theatre of Machines, from 1588

Instead of an e-reader, picture your favorite books on a portable Ferris wheel, a lazy susan of knowledge and imagination turned on its side. Supplement your jogging habit with a treadmill that literally mills, converting caloric expenditure into bread flour. Or flip another page to find: bandsaws and bellows powered by rivers; ecological cofferdams; and a fountain that uses hydrostatic pressure to sing the songs of birds, beckoning nightingales to preen beneath its spouting showers. If this sounds like an Arcadian vision of the future, it is a future from the past. Agostino Ramelli’s 1588 Le diverse et artificiose machine (Diverse and artificial machines) features these devices (and about two hundred others) in an intricately illustrated volume. Published in Paris as a bilingual edition dedicated to King Henri III, the French and Italian tome has as much in common with literary texts as mechanical manuals. Ramelli’s designs gain their value not from practicality and efficiency (few were ever built), but from “classical gravitas”, visual imitations of the antiquity that Renaissance scholars and artists were busy rediscovering and, in turn, inventing.

Japanese multiplication method is fascinating

Japanese multiplication

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 15, 2023

[how it works: https://t.co/aHy9rdPmCg]

[📹 mathswithmisschang: https://t.co/6NBcsp2rTP]pic.twitter.com/W41oFEo3y1