Stuart Little movie reveals long-lost Hungarian art

A long-lost avant garde painting was returned to Hungary after nine decades thanks to a sharp-eyed art historian, who spotted it being used as a prop in the Hollywood film Stuart Little. Gergely Barki, a researcher at Hungary’s national gallery in Budapest, noticed Sleeping Lady with Black Vase by Róbert Berény as he watched television with his daughter Lola. “I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw Bereny’s long-lost masterpiece on the wall behind Hugh Laurie. I nearly dropped Lola from my lap,” said Barki. The painting disappeared in the 1920s, but Barki recognised it immediately even though he had only seen a faded black-and-white photo from an exhibition in 1928. A former set designer had bought it for next to nothing in an antiques shop in Pasadena.

PhD student solves 2,500-year-old Sanskrit problem

A Sanskrit grammatical problem which has perplexed scholars since the 5th Century BC has been solved by a University of Cambridge PhD student. Rishi Rajpopat, 27, decoded a rule taught by Panini, a master of the ancient Sanskrit language who lived around 2,500 years ago. Sanskrit is mostly spoken in India by an estimated 25,000 people, the university said. Mr Rajpopat said he had "a eureka moment in Cambridge" after spending nine months "getting nowhere". "I closed the books for a month and just enjoyed the summer - swimming, cycling, cooking, praying and meditating," he said. "Then, begrudgingly I went back to work, and, within minutes, as I turned the pages, these patterns starting emerging, and it all started to make sense."

A kidnapping negotiator gets his biggest test: saving his own wife

Some of the kidnappers were barely teenagers, shooting rifles into the air as they marched hundreds of hostages through a thorn forest to find cellphone service. They would soon relay a message to the man known as “the negotiator”—a corn farmer and part-time newspaper reporter who has become an unlikely go-between for families of the abducted and the kidnappers demanding payment. This call was different. The kidnappers had the negotiator’s wife. When the phone call came in, 46-year-old Abdullahi Tumburkai was sitting on his bed in the dark some 100 miles away. He could hear gunfire, he said. He had been on dozens of tense calls to help free abducted family, friends and neighbors before, and he tried to remember to keep his voice steady and calm.

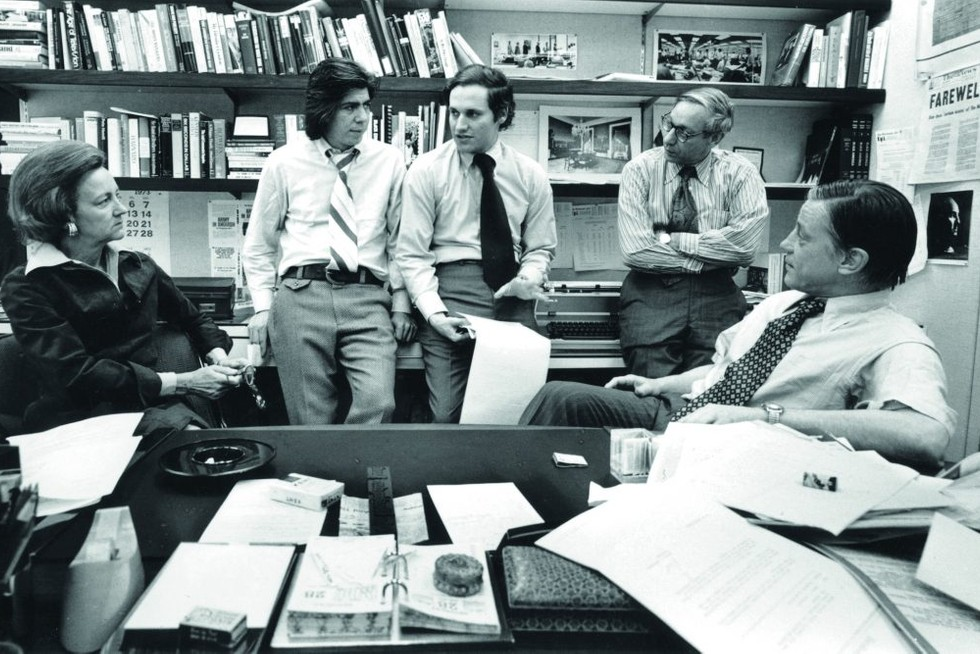

How one-third of “The Watergate Three” got written out of journalism history

For generations of young reporters, the men who brought down Richard Nixon, who exposed Watergate, were two in number: Woodward and Bernstein. Woodstein, if you wanted people to know you’d mastered the lingo. But there was a third man involved -- an editor named Barry Sussman, who helped mastermind the story. He died recently at the age of 87, and while his passing earned some notice, it wasn’t commensurate with the impact of his work. In the half-century since the Watergate break-in, what was originally the Watergate Three has shrunk to become, in the popular imagination, the Watergate Two. Sussman was uniquely shortchanged by the transformation of the Post’s Watergate coverage from news story into cultural artifact.

The deacon and the dog

The memory that sticks out to Jim Murphy from the screwiest bank robbery in New York City’s history is not the slow drive down a dark road at JFK Airport, with a shotgun leveled inches from his head, or the scrum of onlookers hooting and hollering every time hostage-taker John Wojtowicz stood toe-to-toe with negotiators. It’s not the salacious details of Wojtowicz’s backstory—man robs bank to pay for his “wife’s” sex-change operation in attempt to woo him/her back—or the pop of Murphy’s revolver as he shot Sal Naturale during a struggle for control of Naturale’s shotgun. It isn’t the kiss on the cheek from the hostage he had just saved, or the night, a few years later, that he saw Lance Henriksen play a grim-faced caricature of him in Dog Day Afternoon.

No one really knows what’s inside the smallpox vaccine

At the heart of history’s most successful eradication campaign is a mystery. The smallpox vaccine—now also being deployed against monkeypox—contains a live virus that confers immunity against multiple poxviruses. But it is not smallpox or a weakened version thereof. Nor is it monkeypox. Nor is it cowpox, as suggested by the vaccine’s famous origin story involving pus taken from an infected milkmaid to immunize an 8-year-old boy. It is something else entirely: a unique poxvirus whose origins have been lost, or perhaps never known at all. Scientists call it vaccinia, and it is pretty much found only in the vaccines. No one knows where vaccinia came from in nature. No one has ever found its animal reservoir. No one knows quite what vaccinia is—even as it has been used to inoculate billions of people and saved hundreds of millions of lives.

A 4,000-year-old receipt for beer

Beer is one of the oldest drinks humans have produced, dating back to at least the 5th millennium BC in Iran. This is a 4,000 year old beer receipt recording a purchase from a brewer, c. 2050 BCE from the Sumerian city of Umma in ancient Iraq [read more: https://t.co/ErHmcM3bzX] pic.twitter.com/kcaKrpxFTD

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) December 21, 2022