Spanish athlete emerges from a cave after 500 days

A 50-year-old Spanish extreme athlete who spent 500 days living 70 metres deep in a cave outside Granada with no contact with the outside world said the time flew by, and she did not want to come out. Beatriz Flamini, an elite sportswoman and mountaineer, is said to have broken a world record for the longest time spent in a cave, in an experiment closely monitored by scientists seeking to learn more about the capacities of the human mind and circadian rhythms. She was 48 when she went into the cave, and celebrated two birthdays alone underground. She began her challenge on Nov. 20, 2021 — before the outbreak of the Ukraine war, the resultant cost of living crisis, the end of Spain's lengthy COVID-19 mask requirement and the death of Britain's Queen Elizabeth II. She emerged into the light of spring in southern Spain on Friday wearing dark glasses, carrying her equipment and smiling broadly. She described her experience as "excellent, unbeatable," and said that time had flown by. "When they came in to get me, I was asleep. I thought something had happened. I said: 'Already? Surely not.' I hadn't finished my book."

How did people wake up on time before alarm clocks?

Dan Lewis explains: "The first mechanical alarm clock was patented in the late 1800s, but this was before the Industrial Revolution. Society’s ability to mass-produce mechanical ways to wake us up wasn’t coming until at least the 1920s. Workers, though — and that constituted someone in just about every family — still needed to be woken up each morning. Absent a mechanical solution, how did people wake up in the morning? One answer? A person with a very long stick. In England, at least, these people were called “knocker-ups” or “knocker-uppers,” a name which described the act they’d perform each morning. The knocker-up would come to your window, give it a few taps, and then wait to make sure you had awoken. If you had, great — he or she moved onto the next house. If not, they were typically charged with trying again, as knocker-ups were often only paid if they waited to ensure that the customer had, indeed, woken up. The job paid a few pence a week and was often performed by the elderly, by women, or by off-duty policemen.

Massive collection of classic cars found in a Dutch warehouse

In the car-collector world, a "barn find" is a classic old car found in someone's barn, often covered in dust but in good shape for its age. One of the largest collection of such cars ever seen is being auctioned off — more than 230 classic cars, including Ferraris, Alfa-Romeos, Jaguars, Rolls-Royces and more, in the personal collection of someone known only as Mr. Palmen, who collected them in a church and two warehouses near Rotterdam over the course of more than 40 years. He reportedly started most of them regularly so the engines wouldn't seize, but apparently drove very few of them. Jalopnik says the list of classics "is honestly intimidating. From a 1912 Singer Convertible and a 1927 Ford A Roadster to a 1984 Ferrari 400 Automatic i and a 1995 Jaguar XJ-S 4.0 Convertible, there is a wide variety of American and European machinery ranging from the 1910s through the 2000s." According to the auctioneer handling the sale, "it is unlikely that anyone will ever see a collection of this caliber and condition again in their lifetime."

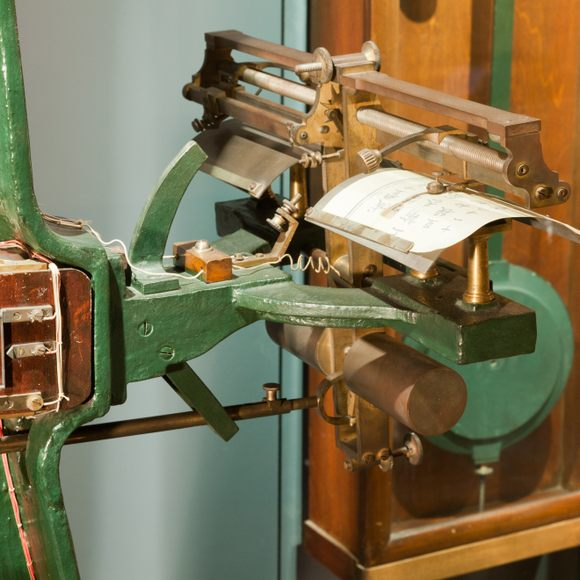

In the 1800s there was a fax machine called the pantelegraph

The pantelegraph was an early form of facsimile machine developed by Giovanni Caselli and used commercially in the 1860s that transmitted over telegraph lines, and was able to transcribe handwriting, signatures, or drawings. It used a regulating clock with a pendulum which made and broke the current for magnetizing its regulators; the pendulum weighed eighteen pounds and was mounted on a frame that was a little over six feet high. Two messages were written with insulating ink on two fixed metal plates — one plate was scanned as the pendulum moved to the right and the other as the pendulum moved to the left, so that two messages could be transmitted per cycle. Napoleon III visited Caselli's workshop and was so taken by the device that he gave him access to telegraph lines, and later, Russian Tsar Alexander II installed an experimental service between his palaces in Saint Petersburg and Moscow between 1864 and 1865.

Small towns in the US are offering cash to families that move there

Nebraska Public Media reports on the growing phenomenon of small towns offering cash to people who relocate: "Topeka will give you up to $15,000 for moving to the capital of Kansas to work for certain employers, or for remote work. Buy a new home in Newton, Iowa, and the city will cut you a $10,000 check. Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Quincy, Illinois, also offer awards aimed at bringing in new residents. So far, the programs seem successful at grabbing the attention of potential residents. The offers stand out and make a move to an underdog area seem more palatable. But it’s unclear whether one-time awards can bring small towns and cities back from the brink. In Curtis, where the incentives have been in place for years, several houses stand on a bluff overlooking a golf course with a pond. All of the houses were developed on lots that the city gave away as part of the incentive program. Almost all of the lots in the program have been claimed, and 12 houses have been built. In such a small town, Lee says those families have impacted the community."

When typewriters took to the sky

Robert Messenger, a typewriter fan, writes: "In its June 1920 edition, Typewriter Topics drew the attention of its American readers to 'The Business Man’s Aeroplane' taking to the skies over England. Topics said the plane was equipped as an office, and illustrated the point with photographic evidence provided by the English Speaking Union, an international educational charity. In the same issue of Tropics the Corona advertisement, showing a man using the folding portable while flying in a Curtis JN-4 ‘Jenny,’ made its first appearance. The aircraft in Topics was a Westland Limousine, a single-engined four-seat light transport biplane, powered by a Rolls-Royce Falcon Mark III engine. It was developed by civil aviation pioneer Robert Arthur Bruce as the “private motor car of the air” in which “a business man can dictate letters to his typist and sign the completed letter while on his way to his appointment.” The first mention of an aircraft specially fitted for typewriter use that I can find appeared on the front page of the London Daily Mirror on January 28, 1919, with a large halftone under the heading 'Up-to-Date Business Man’s Flying Office.'"

Bobbie the Wonder Dog walked 4,000 kms to reach his family

The story of Bobbie the Wonder Dog, who walked a distance of at least 4,105 km through U.S. plains, desert, and mountains, swimming in rivers and even crossing the Continental Divide in the coldest part of winter, to finally return home to his family https://t.co/J3sqF0aSrr pic.twitter.com/GOwWYa6zFL

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) April 20, 2023