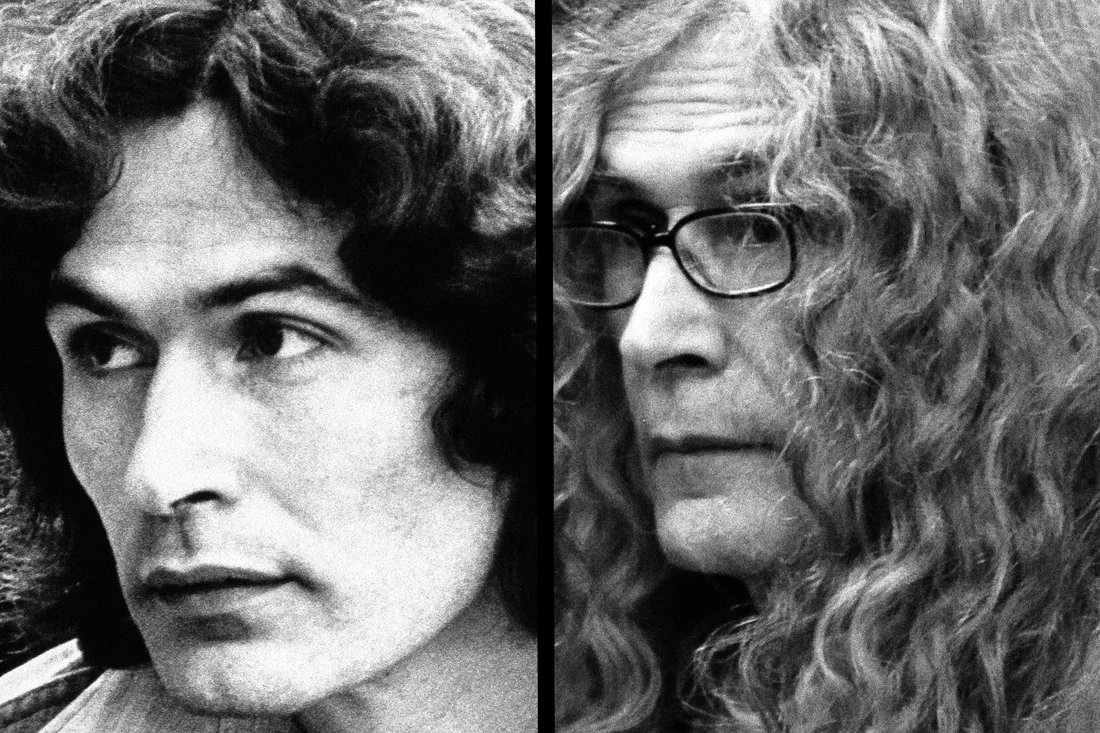

She survived the Dating Game killer and then asked him why

From The Cut: "The second time I met Rodney Alcala was on March 23, 2013. We were inside one of the North Infirmary Command buildings on Rikers Island, two months after he’d been sentenced for raping and murdering Cornelia Crilley and Ellen Jane Hover, both women in their early 20s and living in New York City, in the 1970s. He was trailed by a prison guard, his baggy dove-gray jumpsuit hung loosely around his bony frame. His once black hair had turned the color of steel wool, still in greasy ringlets streaming past his shoulders. He was so much shorter than I remembered. Glasses that had been round wires were now rectangular. As he stiffly shuffled toward me, I felt stage fright — then a surge of real fright when I realized he wasn’t handcuffed.The first time was in April 1969, on a wet day on St. Marks Place in the East Village. I was 14 years old."

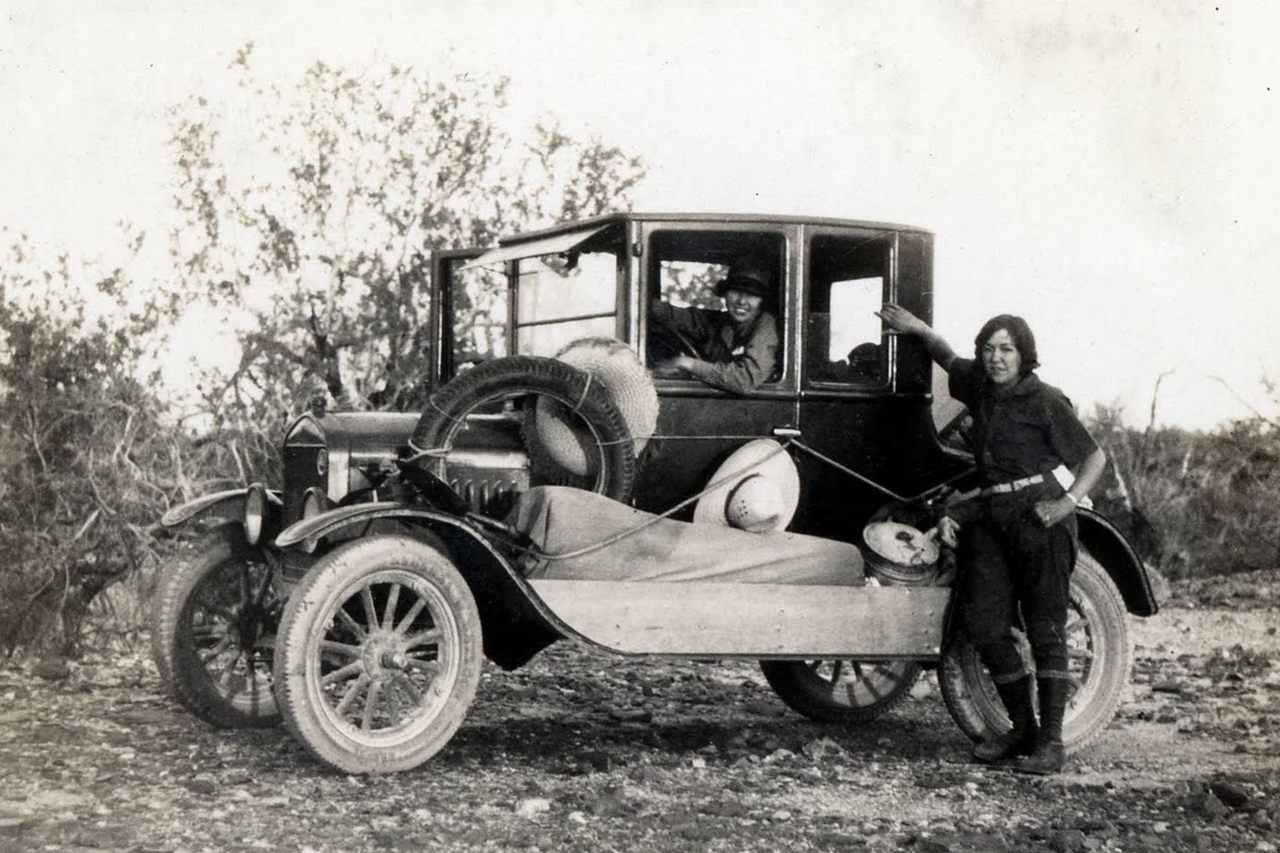

These adventurous women photographed the California desert in the 1920s

From Atlas Obscura: "Smith served as the postmaster for the town of Mecca, California, in the southern Coachella Valley, for almost a decade starting in 1926. It was in that capacity that she came in frequent contact with the unconventional characters, such as prospectors, who lived and worked in the harsh desert region to the east. She also aspired to take photos with her Graflex camera to sell as picture postcards, a popular product of the time. Much of her free time was therefore spent journeying to rugged and remote desert areas such as Mecca Mud Hills, Desert Hot Springs, and the Salton Sea by foot, burro, or Ford Model T.. Her travel companion, Graves, had come to California from Tennessee for her health (and to escape an unpleasant family situation). Together, Smith and Graves risked travel unchaperoned, often donning men’s clothing."

The Herculean efforts involved in the renovation of Notre-Dame cathedral

From GQ: "Notre-Dame’s medieval artisans—the blacksmiths who forged the axes, hewers who squared the timber, joiners who connected the timbers without nails or screws—represented a savoir-faire, or expertise, that has all but died out in the age of Ikea. Masons cut limestone from quarries near Paris and transported blocks by horse cart to the capital. Foresters searched dense woodlands for the straightest and sturdiest oak trees and felled them with steel-tipped axes. They used ropes and scaffolding made of branches to hoist the timber and stone. The roof’s charpente was perhaps their greatest creation. Yet Fromont told me that, until recently, it had never been the subject of serious scholarly study. Hidden from view and difficult to access, it appears to have been largely overlooked by academics, who preferred to focus on Notre-Dame’s limestone arches."

The thing to remember about Kafka is that his work is supposed to be funny

From the LRB: "It has been said of Kafka’s work that the thing to remember is that it is funny. Kafka was known to laugh uncontrollably when reading his work aloud to friends. But what kind of funny is he? Borges described Hawthorne’s story ‘Wakefield’ as a prefiguration of Kafka, noting ‘the protagonist’s profound triviality, which contrasts with the magnitude of his perdition’. Part of the point here is an incongruity of scale – a natural structure of the comic, a way of relating to the cosmic. We might think here of Metamorphosis but also of the petitioner in The Trial who spends his whole life waiting at the Door of the Law, a door that is just for him, but through which he is never allowed entry. Or we might think of Kafka’s dog (or his ape, or mouse, or burrowing animal), who takes his life as seriously, and thinks it over as analytically, as a human.

The story of Henry Trigg and the coffin in the roof

From Amusing Planet: "Henry Trigg lived in early 18th-century England. The story goes that one evening after a few drinks at the tavern, Henry and his friends were heading home along a route that passed by the churchyard. While walking past the gravestones they saw some body snatchers at work, removing the remains of the newly-buried corpse for sale to surgeons. The sight disturbed Henry so deeply that he resolved to prevent such a fate from befalling his own body after death. Determined, Henry wrote a will where he requested that his body be placed in a coffin, and instead of burying at the churchyard, be placed upon the purlins and underneath the rafters of his barn. Henry added that his body should remain there for a minimum of thirty years, after which he believed he would rise from the dead and reclaim the estate that legally belonged to him."

Zooming in on the Pillars of Creation

Zoom into the Pillars of Creations with a combination of ground based telescopes and Hubble.

— Wonder of Science (@wonderofscience) November 5, 2024

These columns of gas and dust that span roughly 4 to 5 light-years are sculpted and eroded by stellar winds from the nearby massive stars.

📽: NASA, ESA/Hubblepic.twitter.com/lI0l7fJROX

Acknowledgements: I find a lot of these links myself, but I also get some from other newsletters that I rely on as "serendipity engines," such as The Morning News from Rosecrans Baldwin and Andrew Womack, Jodi Ettenberg's Curious About Everything, Dan Lewis's Now I Know, Robert Cottrell and Caroline Crampton's The Browser, Clive Thompson's Linkfest, Noah Brier and Colin Nagy's Why Is This Interesting, Maria Popova's The Marginalian, Sheehan Quirke AKA The Cultural Tutor, the Smithsonian magazine, and JSTOR Daily. If you come across something interesting that you think should be included here, please feel free to email me at mathew @ mathewingram dot com