Phyllis Latour: The secret life of a WW2 heroine revealed

From Sanchia Berg for the BBC: "In the summer of 1944, in a village in German-occupied western France, a slim young woman with dark hair and grey-green eyes sat in a building with a wireless set, tapping out messages in Morse code. She was an agent in the Special Operations Executive, known as Churchill's Secret Army. Her codename was Genevieve and she was sending urgent messages back to London. The messages being sent by Genevieve were vital intelligence, as they included precise locations for the RAF to bomb, as well as where to drop equipment. Working behind German lines, as the fighting grew closer, was incredibly dangerous, but she never lost her nerve. Genevieve's real name was Phyllis Latour. After she married, she became known as Pippa Doyle, and rarely spoke about her wartime career."

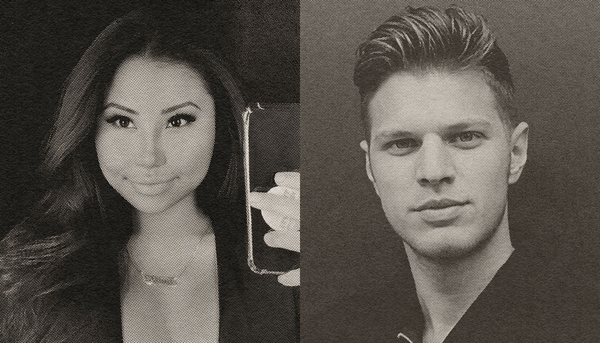

Unraveling 40 years of sexual misconduct at a single California high school

From Matt Drange for Insider: "Clara didn't think much of it when the social science teacher gave her his phone number. She'd met Alex Rai in her fifth-period journalism class. He was friends with the journalism teacher, Eric Burgess, and often stopped by Room 16 during his prep period to kill time. Burgess introduced Rai to Clara, telling her that Rai had been his student a decade before. Burgess thought they'd get along. In the weeks that followed, Rai would perch on Clara's desk, leaning over as he asked about her day and who she hung out with after school. He's only a few years older than my sister, Clara thought when Rai texted her one day after volleyball practice."

Ghost in the machine: How fake parts infiltrated airline fleets

From Bloomberg: "This spring, engineers at TAP Air Portugal’s maintenance subsidiary huddled around an aircraft engine that had come in for repair. The exposed CFM56 turbine looked like just another routine job for a shop that handles more than 100 engines a year. Only this time, there was cause for alarm. Workers noticed that a replacement part, a damper to reduce vibration, showed signs of wear, when the accompanying paperwork identified the component as fresh from the production line. On June 21, TAP pointed out the discrepancy to Safran SA, the French aerospace company that makes CFM engines together with General Electric. Safran quickly determined that the paperwork had been forged. The signature wasn’t that of a company employee, and the reference and purchase order numbers also didn’t add up."

Editor's note: If you like this newsletter, I'd be honoured if you would help me by contributing whatever you can via my Patreon. Thanks!

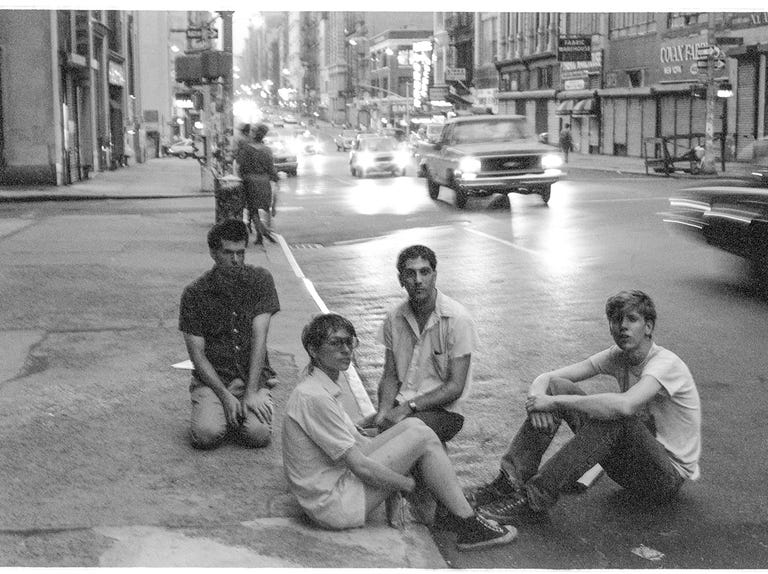

Sonic Youth's Thurston Moore writes about his favorite New York apartment

From Thurston Moore: "After looking at some real ratholes, I settled on a third-floor walkup at 512 East Thirteenth Street between Avenues A and B. The rent was $110 per month, a manageable enough sum—if I could land a job. The building was typical for the East Village in 1978, especially for the stretch that residents called Alphabet City. No buzzer system at the door; tiny black-and-white-tiled floors, all chipped and grimy. The tenant above me was a barely functional ex-con and drug addict who had a couple of high-strung rottweilers, which he would drunkenly whip and yell at throughout the night. Above him lived an alcoholic couple who stumbled up and down the stairs. When I crossed their path, they would urge me to take a sip from their sloshing bottle of booze."

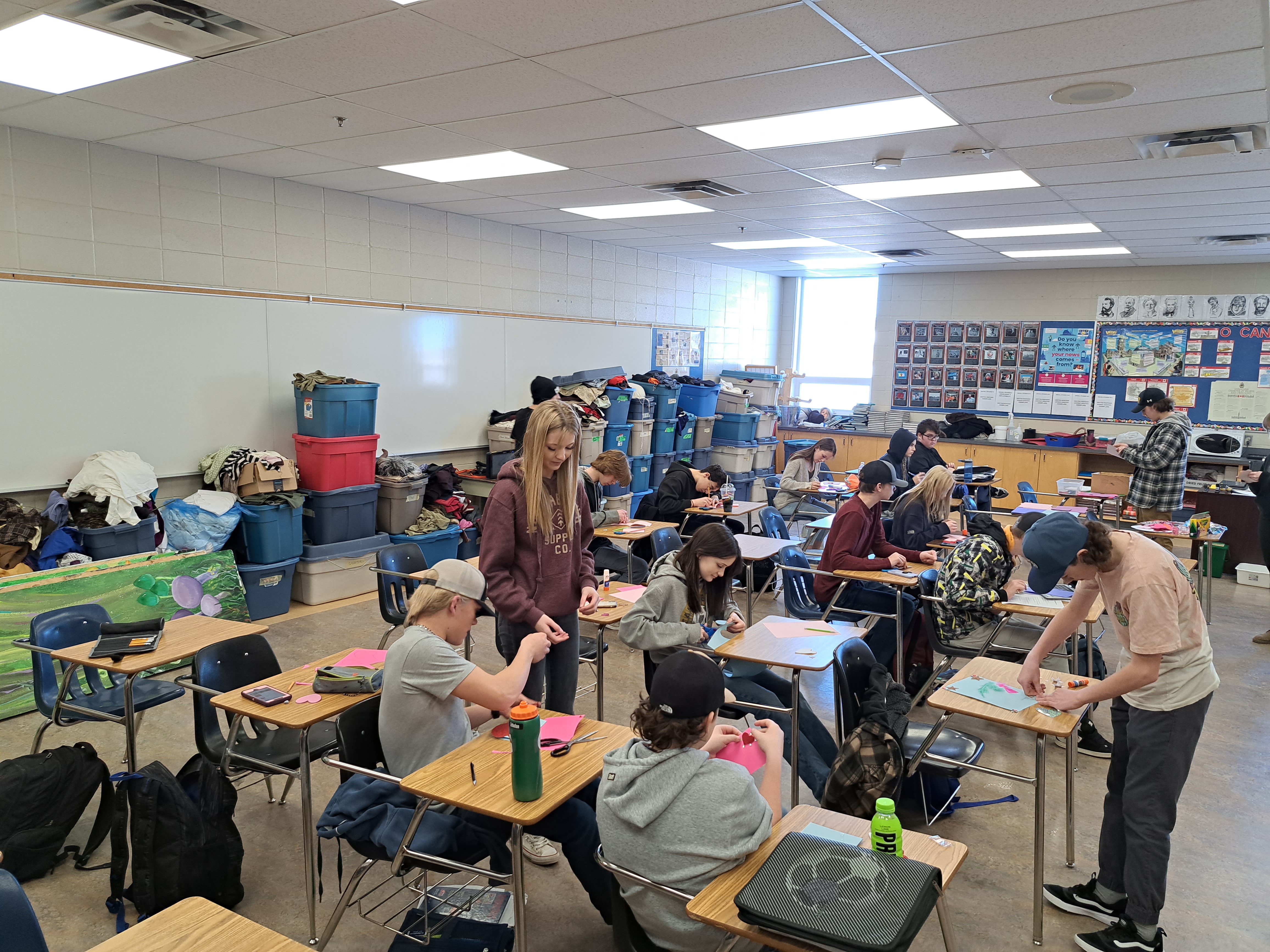

When I got paid to spy on people while they worked

From Kira Witkin for Esquire: "For the eighth time today, I ask to store my baby’s umbilical cord blood at the stem cell bank. “I hope you don’t mind,” I tell the saleswoman on the phone. “My husband gave me a list of questions to ask.” “I know how that is, Linda,” the saleswoman says, but she doesn’t. My name is not Linda. I am not married, pregnant, or considering freezing my unborn child’s stem cells. I can barely afford shampoo, much less a $6,000 vial of my own bodily fluids. But if I pretend for 15 minutes, I’ll get $8. At the kitchen table of my fifth-floor Harlem walk-up, a roach trap beneath my foot, I stare at a printout titled “CHEAT SHEET.” I read from a script; the responses might determine whether or not this saleswoman gets fired."

This Christopher Nolan film made money from a cornfield planted for the movie

From Dan Lewis at Now I Know: "Interstellar tells the story of Earth about fifty years in the future. A widespread blight has killed most food crops — only corn and okra can still be grown, and okra is quickly going the way of the dodo. The protagonist, Joseph Cooper, is a former pilot who became a farmer, and not entirely by choice — the world has effectively shut down all scientific exploration. With a budget north of $100 million, Nolan wanted to make his sci-fi film feel as real as possible. Instead of using CGI for Cooper’s farm, the filmmaker and his crew decided to use real corn fields. They spent $100,000 to grow corn in Western Canada, where the film was ultimately shot. When filming came to a close, there was still a lot of corn left over — more than enough to cover the cost of growing it in the first place, and then some."

The dance of a thousand hands

From Massimo on Twitter: "The “Dance of the thousand-hand Quanyin” is possibly the most famous & most spectacular visual display in which geometry & synchronization create a kind of effective optical illusion"