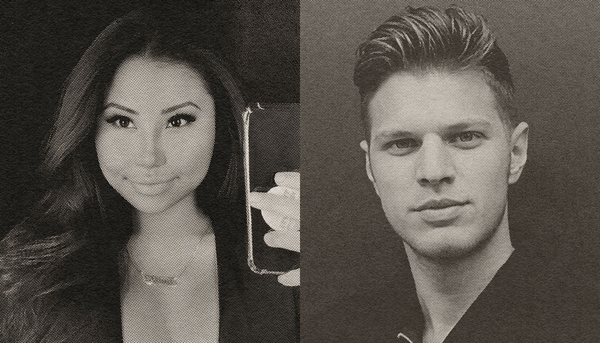

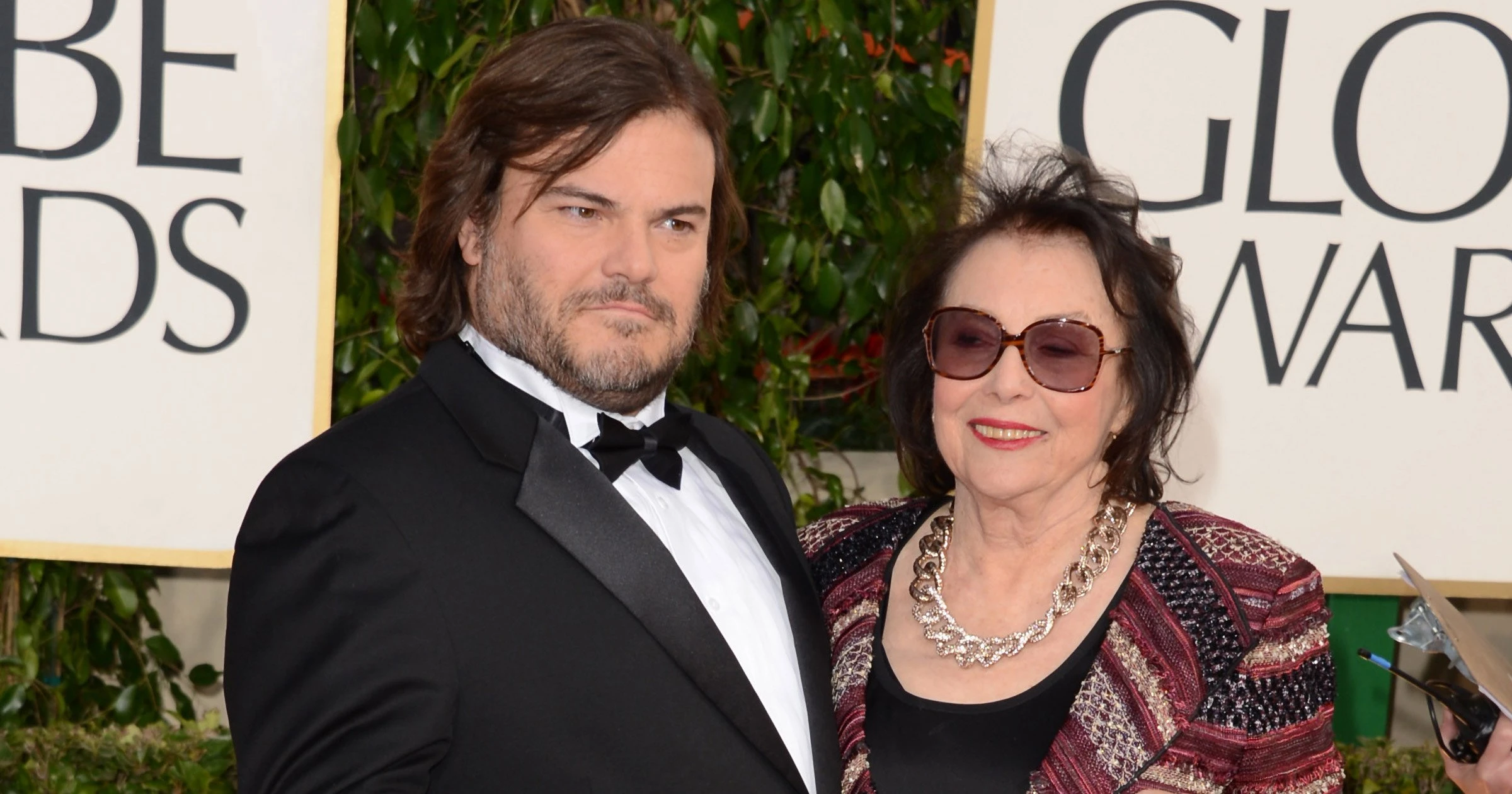

How Jack Black's mother helped save NASA's Apollo 13 mission

As a teenager, Judith Love Cohen went to a guidance counselor to talk about her future and professed her deep love of math. But the counselor had other advice. She said: “I think you ought to go to a nice finishing school and learn to be a lady.” Instead, Cohen pursued her dreams. She studied engineering at USC and later helped design the program that saved the Apollo 13 astronauts. In retirement, Cohen produced books encouraging young girls to follow in her footsteps. Although her son, Jack Black, is certainly the most famous of the family, his mother has a remarkable story all her own.

Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead mansion sells, but the tenants refuse to leave

The Cotswold mansion where Evelyn Waugh wrote Brideshead Revisited has sold at auction for £3.16m despite buyers being warned that sitting tenants – who are paying a weekly rent of £5 a week – are refusing to leave the property. Piers Court, at Stinchcombe, a village about halfway between Bristol and Cheltenham, was sold to an unnamed bidder in an online auction on Thursday after the owner defaulted on a loan secured against the eight-bedroom, six-bathroom property. The sale went ahead despite the tenants, who described themselves as “Evelyn Waugh superfans”, refusing to vacate the property which they rent for just £250 a year in a deal with its previous owner, Jason Blain, a former BBC executive who bought the property for £2.9m in 2019.

From chocolate gramophones to MP3s: The history of sound in pictures

The Chocolate Record Player (1902), a Stollwerck gramophone, was a novelty toy designed to play chocolate discs. Stollwerck had been founded in Germany in 1839, and by the end of the century it was one of the world’s biggest confectionary companies. The novel idea was that the tiny (3 1/16-inch; 7.6-cm), vertically cut chocolate records could be eaten after use. This was nonetheless a working gramophone: the ornate green tin model was powered by a Junghauns clock motor. It was a short-lived novelty, and one of the more whimsical experiments in the sound recording and playback history chronicled in The Art of Sound: A Visual History for Audiophiles, a book by author and musician Terry Burrows (thanks to David Weinberger for sending in this item!)

The legal no-man's-land in Yellowstone known as the "zone of death"

Imagine Daniel and Henry are vacationing in Yellowstone National Park, and set up camp in the 50 square miles of the park that are in Idaho (unlike most of the park, which is in Wyoming). They get into a fight and Daniel winds up killing Henry. At his trial, he invokes his right, under the Sixth Amendment, to a jury composed of people from the state where the murder was committed (Idaho) and from the federal district where it was committed. But the District of Wyoming has purview over all of Yellowstone. So Daniel has the right to a jury composed entirely of people living in both Idaho and the District of Wyoming — that is, people living in the Idaho part of Yellowstone. No one lives in the Idaho part of Yellowstone. A jury cannot be formed, and Daniel walks free.

Where does all the cardboard come from?

Before it was the cardboard on your doorstep,it was coarse brown paper, and before it was paper, it was a river of hot pulp, and before it was a river, it was a tree. Probably a Pinus taeda, or loblolly pine, a slender conifer native to the Southeastern United States. “The wonderful thing about the loblolly,” a forester named Alex Singleton told New York Times writer Matthew Shaer this spring, peering out over the fringes of a tree farm in West Georgia, “is that it grows fast and grows pretty much anywhere, including swamps” — hence the non-Latin name for the tree, which comes from an antiquated term for mud pit. “See those oaks over there?” Singleton went on. “Oaks are hardwood, with short fibers. Fine for paper. Book pages. But not fine for packaging, because for packaging, you need the long fibers. A pine will give you that. An oak won’t.”

The tiny medieval town that Panettone built

It’s September at the Fiasconaro factory in Castelbuono, Sicily, months before panettone starts to appear on Christmastime tables worldwide, but all of Fiasconaro’s loaves are already spoken for. In dumpster-size tubs lined up along the walls in the mixing room, yellow, webby dough practically spills over the edges, waiting to be mixed with candied orange, chocolate, hazelnuts, apricots. On a slower production day, the bakery will produce 12,000 kilograms, or roughly 26,000 pounds, of dough. During the holidays, that number skyrockets to 16,000 kilograms, or 35,000 pounds of dough, per day. The factory sits on top of the hill above the center of Castelbuono, a cobblestoned 14th-century village in the middle of Sicily’s mountainous Madonie National Park.

An incredible level of detail in a single photo

This is the level of detail you can get from a 365-Gigapixel picture

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) December 19, 2022

[source, read more: https://t.co/IDSqMKQWLv] pic.twitter.com/UQuY1lX7KQ