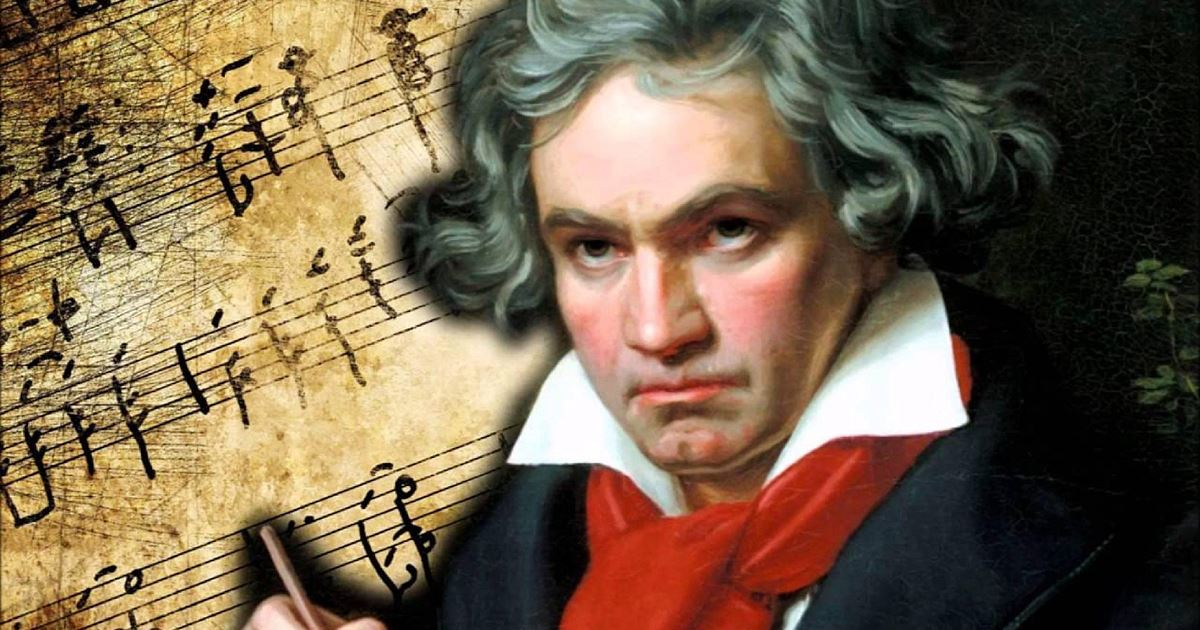

DNA from Beethoven’s hair unlocks family secrets

It was March 1827 and Ludwig van Beethoven was dying. As he lay in bed, wracked with abdominal pain and jaundiced, grieving friends and acquaintances came to visit. And some asked a favor: Could they clip a lock of his hair for remembrance? The parade of mourners continued after Beethoven’s death at age 56, even after doctors performed a gruesome craniotomy, looking at the folds in Beethoven’s brain and removing his ear bones in a vain attempt to understand why the revered composer lost his hearing. Within three days of Beethoven’s death, not a single strand of hair was left on his head. Ever since, a cottage industry has aimed to understand Beethoven’s illnesses and the cause of his death. Now, an analysis of strands of his hair has upended long held beliefs about his health. The report provides an explanation for his debilitating ailments and even his death, while raising new questions about his origins and hinting at a dark family secret.

What were Neanderthals really like—and why did they go extinct?

When limestone quarry workers in Germany’s Neander Valley discoveredfossilized bones in 1856, they thought they’d uncovered the remains of a bear. In fact, they’d stumbled upon something that would change history: evidence of an extinct species of ancient human predecessors who walked the Earth between at least 400,000 and 40,000 years ago. Researchers soon realized that they had already encountered these human relatives in earlier fossils that had been found, and misidentified, throughout the early 19th century. The discovery galvanized scientists eager to explore new theories of evolution, sparking a worldwide fossil hunt and tantalizing the public with the possibility of a mysterious sister species that once dominated Europe. Now known as Neanderthals—so named by geologist William King—Homo neanderthalensis are humans’ closest known relatives.

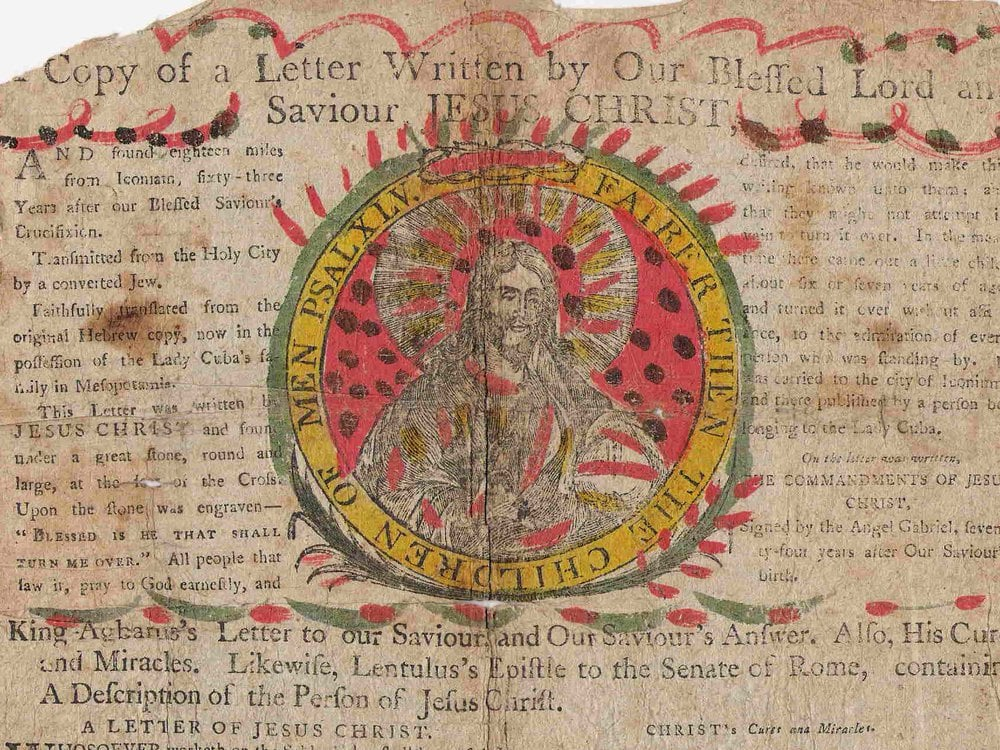

Chain letters used to raise funds for orphans and send messages from God

One predecessor to chain letters is the so-called “Letter from Heaven,” emerged during or prior to the medieval period. Marketed as messages from Jesus himself, these purportedly divine missives conveyed instructions (celebrate the Sabbath on Sunday rather than Saturday, fast on five Fridays each year, do not gather vegetables on Sundays) and conferred protection on those who sent them to others. Some claimed “to have fallen from the heavens,” while others were said to be written in Jesus’ own blood. An English version dated to 1795 declared “[H]e that publisheth it to others, shall be blessed of me, and though his sins be in number as the stars of the sky, and he believe in this he shall be pardoned; and if he believe not in this writing, and this commandment, I will send my own plagues upon him, and consume both him and his children, and his cattle.”

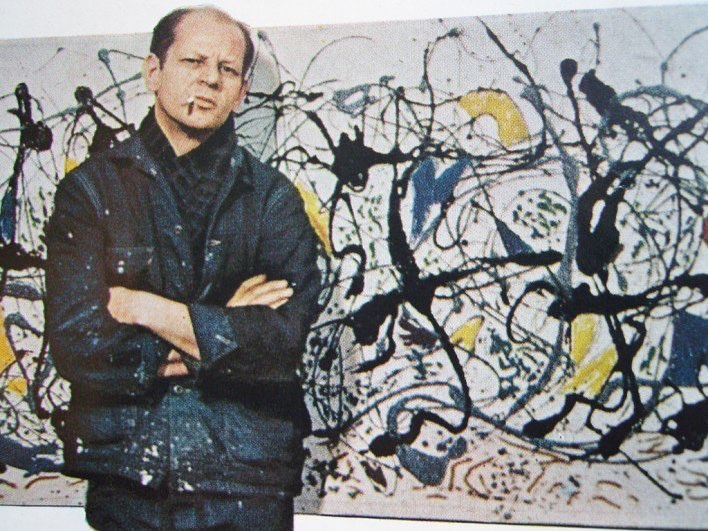

A Jackson Pollock painting worth $54M was discovered in a police raid

To say Bulgarian officials found a lost Jackson Pollock painting during a raid on an art-trafficking ring wouldn’t be exactly accurate—you have to know something exists to consider it missing. However, in an even more dramatic fashion, they did discover a never-before-seen, previously undisclosed work from the abstract expressionist while busting an illegal business. Bulgarian officials worked with a Greek anti-crime unit to bust the trafficking ring, which extended from Bulgaria to Athens and Crete. While the Greek outfit found a collection of paintings by famous artists during the raid (the exact creators weren’t disclosed), their Bulgarian counterparts discovered a canvas bearing Pollock’s faint signature. Police sent sent the work to Bulgaria’s National Art Gallery, who authenticated the piece. The Bulgarian experts say the work dates to 1949 and is an uncatalogued original, estimated to be worth €50 million ($54 million) at auction.

Physics experts say we need to assume the future can affect the past

In 2022, the physics Nobel prize was awarded for experimental work showing that the quantum world must break some of our fundamental intuitions about how the Universe works. Many look at those experiments and conclude that they challenge "locality" – the intuition that distant objects need a physical mediator to interact. And indeed, a mysterious connection between distant particles would be one way to explain these experimental results. Others think the experiments challenge "realism" – the intuition that there's an objective state of affairs underlying our experience. After all, the experiments are only difficult to explain if our measurements are thought to correspond to something real. Many physicists agree about what's been called "the death by experiment" of local realism.

How F1 technology has found its way into everyday use

Trung Phan writes: "The combined parts of a single F1 car runs up to $20m (the engine can make up ~90% of the cost). Meanwhile, the top teams employ 100s of people and spend hundreds of millions of dollars a year to win the tiniest edge. McLaren developed a whole division that adapted the race car’s telemetry and control technology to other industries (healthcare, transportation). Over the decades — there’s been a lot of race innovation that has found its way into everyday use. Unsurprisingly, the most visible examples are in road cars, including the push-button ignition, and that was developed because starting an F1 car is quite complicated. The engine has to be brought up to the right temperature before oil is circulated. When ready, the engine itself starts with the push of the button. That last step — a push-button ignition — is widely available now."

A goat brings his friend with him for breakfast

Wait for the cute surprise.. 😉 pic.twitter.com/ui3L6OkUuY

— Buitengebieden (@buitengebieden) April 2, 2023