Caster Semenya on being persecuted by her sport

From the New York Times: "I know I look like a man. I know I sound like a man and maybe even walk like a man and dress like one, too. But I’m not a man; I’m a woman. Playing sports and having muscles and a deep voice make me less feminine, yes. I’m a different kind of woman, I know, but I’m still a woman. I began running competitively as a teenager in South Africa, and by age 18 I was competing on the international stage. In 2009, as I prepared to run in the Berlin World Championships, athletic authorities sent me for some medical testing. Because of my looks, there had been speculation from my fellow athletes, sports officials, the media and fans that I was not what I said I was."

Vladimir Nabokov's fame is thanks in large part to the work of his wife Vera

From Stacy Schiff for The New Yorker: "Vladimir Nabokov was famous at Cornell, where he taught between 1948 and 1959, for a number of reasons. None had anything to do with the literature; few people knew what he had written, and even fewer had read his work. Tearing Dostoyevski to shreds in front of two hundred undergraduates made an impression, as did the pronouncement that good books should not make us think but make us shiver. The fame derived in part, too, from the fact that the professor did not come to class alone. He arrived on campus driven by Mrs. Nabokov, he crossed campus with Mrs. Nabokov, and he occasionally appeared in class on the arm of Mrs. Nabokov, who carried his books. In fact, the man who spoke so often of his own isolation was one of the most accompanied loners of all time."

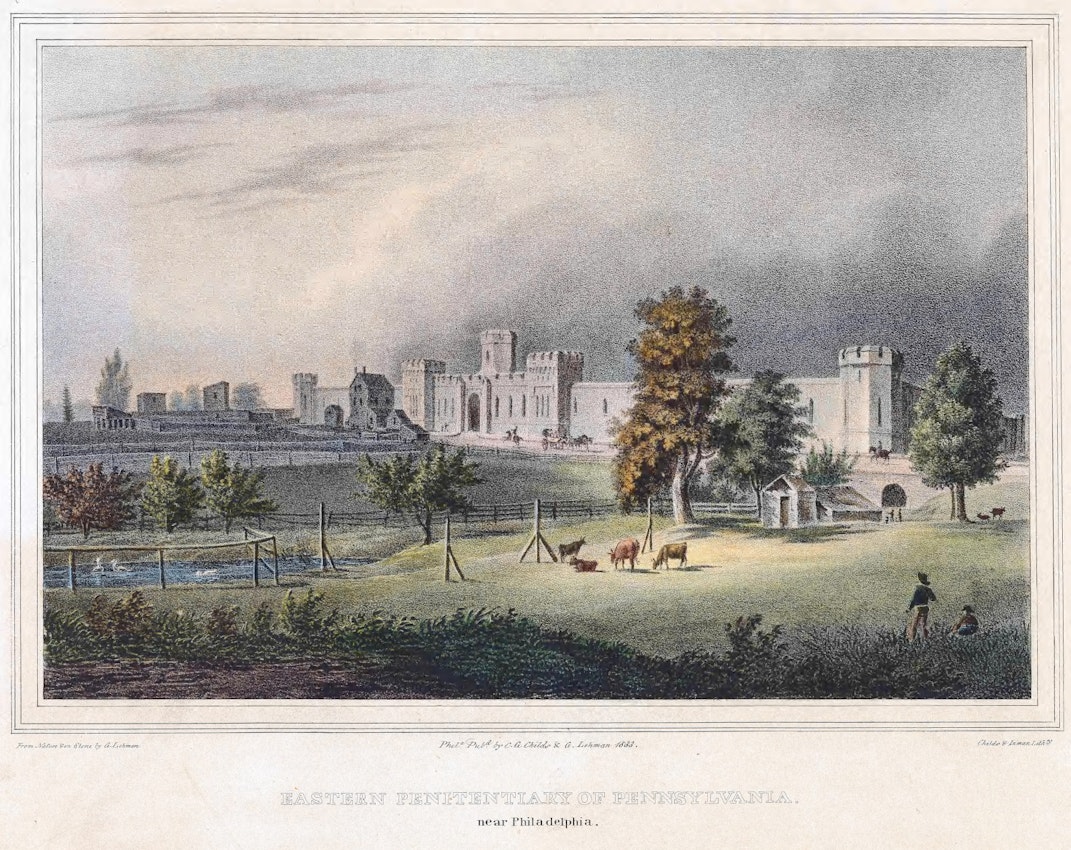

Solitary confinement was an improvement over older methods of punishment

From Jane Brox for Public Domain Review: "The idea of the solitary cell as an integral part of the American prison system arose during the Early Republic, the specific vision of Philadelphia physician and Founding Father Benjamin Rush, who advocated for time in solitude and silence — the active, searching silence of Quakerism — as an alternative to the bodily pain, injury, and humiliation of public hangings and whippings. He saw it as a means not only of punishment but of reformation for housebreakers, forgers, highway robbers, horse thieves, and even murderers, and his vision of justice eventually led to the construction of the world’s first penitentiary, Eastern State."

Editor's note: If are interested in the practical, journalistic, and ethical challenges in getting around paywalls, I wrote a longer version of my note from yesterday on my website. And if you like this newsletter, I'd be honoured if you would help me by contributing whatever you can via my Patreon. Thanks!

Scientists say glass is closer to being a liquid than it is to a solid

From Brian Resnick for Vox: "If you go to a church that’s hundreds of years old and look at the glass windows, you’ll find that the panes are thicker at the bottom of the frame than at the top. That’s because, according to lore, glass is actually a liquid, just one that flows very slowly. This is a myth. The thickness of glass at the base can be explained by how glass panes were manufactured in the olden days, by spinning a glass form into a flat disc. But the myth also does not do glass justice. Glass is so much weirder than a very slow-moving liquid. In fact, scientists still have deep questions about what it fundamentally is."

The humble tomato was feared and reviled for hundreds of years

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/growing-tomatoes-1403296-01-e87fc6443b55423890448cabb12efeba.jpg)

From Annabelle Smith at The Smithsonian: "In the late 1700s, a large percentage of Europeans feared the tomato. A nickname for the fruit was the “poison apple” because it was thought that aristocrats got sick and died after eating them, but the truth of the matter was that wealthy Europeans used pewter plates, which were high in lead content. Because tomatoes are so high in acidity, when placed on this particular tableware, the fruit would leach lead from the plate, resulting in many deaths from lead poisoning. But that wasn't the only reason people feared the tomato. It was also classified as part of the deadly nightshade family, plants that contain toxins called tropane alkaloids."

When mental illness produces outsider art

From Futility Closet: "After several delusional episodes, seamstress Agnes Richter was institutionalized at the University of Heidelberg Psychiatric Clinic in 1893, at age 49. While performing the needlework expected of female patients, she sewed a diary of sorts into a remarkable jacket pieced together of wool and linen. “Writing” in a now-obsolete German script, she recorded brief, enigmatic expressions reflecting life in a psychiatric hospital: I wish to read, I am not big, I plunge headlong into disaster. Her laundry number, 583, appears several times, apparently to ensure that the jacket was not lost during cleaning. Another patient, Mary Lieb, institutionalized periodically at Heidelberg for mania, would sometimes decorate the floors of various rooms with patterns of cloth strips."

A sea creature that is completely transparent

Meet salps, transparent marine creatures

— Massimo (@Rainmaker1973) October 30, 2023

[📹 Andy | Shark Diver / andriana_marine]pic.twitter.com/qtlskxEm27