Alone at the edge of the world

Susie Goodall wanted to circumnavigate the globe in her sailboat without stopping. She didn’t bargain for what everyone else wanted. In the heaving seas of the Southern Ocean, a small, red-hulled sailboat tossed and rolled, at the mercy of the tail end of a tempest. The boat’s mast was sheared away, its yellow sails sunk deep in the sea. Amid the wreckage of the cabin, Susie Goodall sloshed through water seeping in from the deck, which had cracked when a great wave somersaulted the boat end over end. She was freezing, having been lashed by ocean, rain, and wind. Her hands were raw and bloody. Except for the boat, her companion and home for the 15,000 miles she’d sailed over the past five months, Goodall was alone. The 29-year-old British woman had spent three years readying for this voyage. It demanded more from her than she could have imagined. She loved the planning of it, rigging her boat for a journey that might mean not stepping on land for nearly a year. But she was unprepared for the attention it drew—for the fact that everyone wanted a piece of her story.

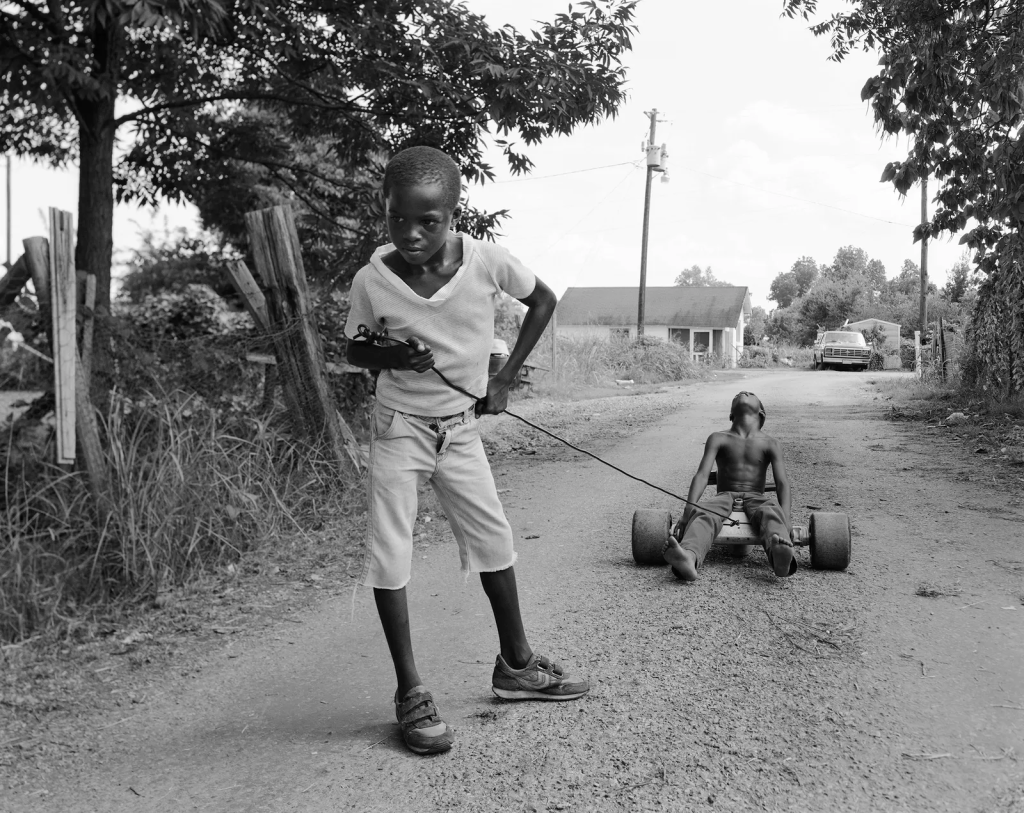

Baldwin Lee’s extraordinary pictures from the American South

A new book—the first-ever collection of Baldwin Lee’s work—and a solo exhibition in New York make the case that he is one of the great overlooked luminaries of American picture-making. Selections from his archive of nearly ten thousand pictures, taken in poor Black communities in the American South between 1983 and 1989, have been exhibited sporadically. “I showed enough to get tenure and raises,” he said recently from his home near the University of Tennessee, where he has been teaching for four decades. Lee was never meant to be a photographer. Born and raised in New York, he was the eldest son of a reluctant Chinatown “noodle king,” who had emigrated from Hong Kong, fought in the U.S. Army on D Day, and had his aspirations to become an architect dashed when he inherited his uncle’s thriving business supplying noodles to Chinese restaurants up and down the East Coast.

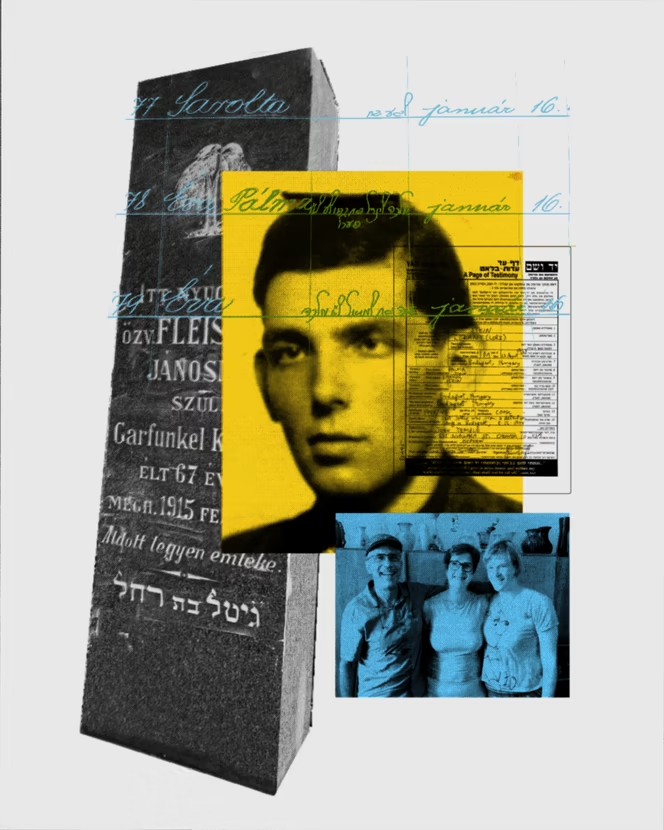

How I finally learned my real name

John Temple tells the story of how an email from a stranger sent him on a quest back in time, to the years before the Holocaust, in search of his family and himself: "The email came from a stranger. “Dear Mr. Temple,” it said. “My name is Andrea Paiss, and I live in Budapest, Hungary. I do not know whether I write to the right person. I just hope so.” It reached me in San Francisco on January 1, 2020, and told of a “Granny,” then 92, who wanted to know what had happened to her cousin Lorant Stein. Andrea had found a document online about Lorant in the Central Database of Shoah Victims at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem. It had been submitted by someone named John Temple. Could I be that same John Temple, she asked? At first my wife, Judith, and I were mistrustful. Could this be an attempt to get money, a scam of some kind? I had filled out the form, but I had no information about relatives still living in Hungary."

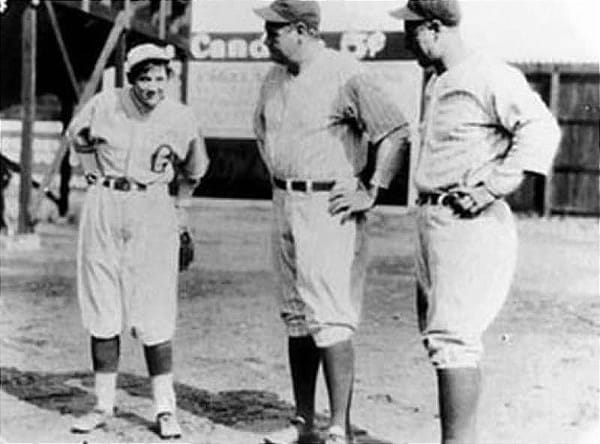

The family that built a ballpark nachos monopoly

Ballpark nachos are a concession stand staple. At Rangers games alone, 600k orders were sold last year, or 1 for every 3.5 fans. For all of Major League Baseball, that statistic would translate to ~13m orders. And for every order, there’s one key figure to thank: San Antonio businessman Frank Liberto. Decades ago, he added a twist to a popular Mexican appetizer and originated the concept of the ballpark nacho. If you’ve purchased nachos at a sporting event or a movie theater, odds are you’ve bought chips, cheese sauce, or jalapeños from the Liberto family’s longtime business. Liberto was a self-described “bald peanut-peddler” who ran a family food business, the Liberto Specialty Company. (Today it’s called Ricos.) His grandfather, Rosario, immigrated from Sicily in the early 1900s, settling in San Antonio and opening a downtown food store in 1909. The store imported Italian coffee and olives, but the company’s most successful venture was peanuts, sold at circuses and local festivals.

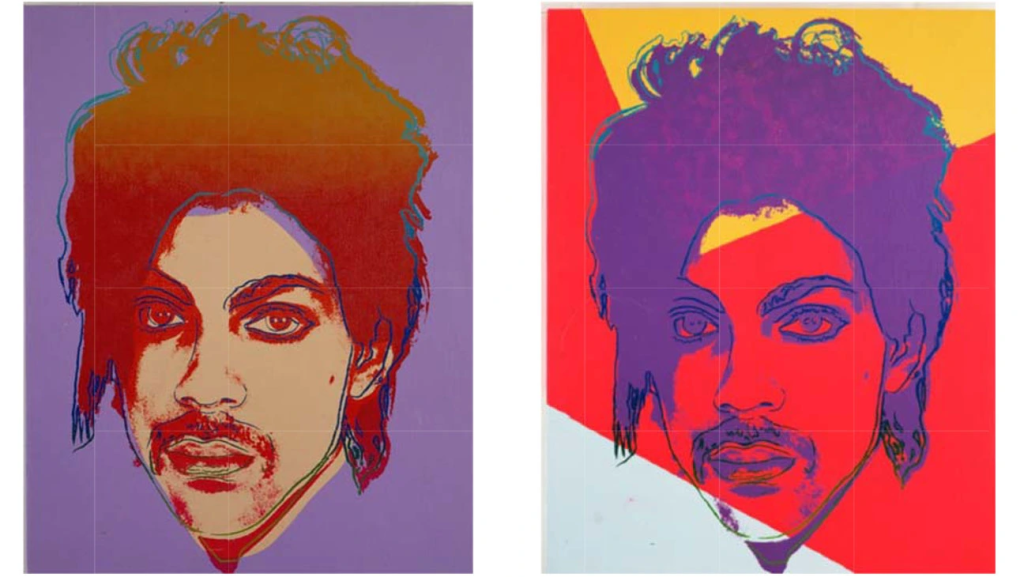

The Andy Warhol case that could wreck American art

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, Lynn Goldsmith, a polymath skilled as a photographer and a musician, took pictures of many of the period’s prominent rock stars, including Prince. One of her images was also enshrined by Andy Warhol, who used a photograph she took of Prince as the basis for his illustrations of the musician. In some legal and art circles, Goldsmith may end up being remembered not so much for her beautiful photographs, but for her legal dispute with the custodians of Andy Warhol’s art. The dispute started when Goldsmith learned that her 1981 photograph of Prince was the basis for Warhol’s illustrations of the rock star. In 2019, a court ruled that Warhol’s image was protected by fair use. The appellate court reversed, principally on the grounds that Warhol’s image is not sufficiently transformative because it “retains the essential elements of its source material” and Goldsmith’s photograph “remains the recognizable foundation.”

Wreck of fabled WWI German U-boat found off Virginia

This past Labor Day, as beachgoers up and down the eastern seaboard of the U.S. enjoyed a sunny holiday at the shore, Erik Petkovic was in the darkened cabin of R/V Explorer some 40 miles off the Virginia coast. Peering into a video monitor linked to a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) some 400 feet below, he suddenly exclaimed, “That’s it! There it is!” The object that caused his excitement was the wreckage of SM U-111, the last World War I-era German submarine to be discovered in U.S. waters. The sleek tube of riveted iron had been part of the Unterseeboot (U-boat) fleet that struck terror in Allied sailors. After the war an American crew brought the captured submarine across the Atlantic in a daring solo voyage that required navigating the icy waters where R.M.S. Titanic had sunk seven years earlier.

Removing a parked car in China is very simple

China is very advanced in removing illegally parked cars. pic.twitter.com/Z22VDENS0k

— Curiously Curious (@justcurious1313) September 30, 2022